My favorite reads of 2025

15 outstanding books

2025 was a pretty rough year on a whole bunch of fronts: from politics to tragedies to just existing in a world that feels increasingly frustrating, I'm not sad to see it in the rearview mirror. But it's easy to dwell on all the bad things that happened, and I think it's important to remember the bright points as well.

For me, 2025 was an excellent year for new books: it brought new reads from a bunch of authors I like and admire and I was introduced to a whole bunch of new authors who I'll now be looking out for.

It's always tempting to look back at the year and see if there's anything that ties everything together into a neat, tidy thread. There usually isn't one: everyone's working in their own corner of the world and aren't necessarily writing to comment on the state of it, but looking over the books that resonated with me the most, I found a couple of things that seemed to overlap some of them.

There was a sense of togetherness that a number of these books seemed to take note of: people coming together to solve a common problem, such as in Garrett M. Graff's The Devil Reached Toward the Sky, Joe Hill's King Sorrow, Annalee Newitz's Automatic Noodle, or qntm's There Is No Antimemetics Division.

There was also a sense of people pushing against these big, intractable problems of the day, or at least an acknowledgement that our view of the world can be warped and shaped by external forces, as in David Baron's The Martians, Alix E. Harrow's The Everlasting, Ken Liu's All That We See or Seem, Ray Nayler's Where The Axe is Buried, There Is No Antimemetics Division, and Daniel H. Wilson's Hole in the Sky.

And in a number of cases, a whole bunch of this year's reads sent their characters into archives to try and figure something out or to gain some insights into the past, as in The Everlasting, King Sorrow, Stephen Graham Jones' The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, R.F. Kuang's Katabasis, and Silvia Moreno-Garcia's The Bewitching. (I'm hoping to write more about that at some point this month.)

I think that says more about me than the books themselves: as we face the coming year with even more challenges and crises ahead of us, I feel like we gravitate toward the stories that offer us some hope for the future, that these stories might, if not lay out a roadmap, hold some solutions for us as we navigate the uncertainty that the future holds. Collectively, these are books about people taking on the big challenges that they face, whether it's ongoing wars, aliens, vampires, dragons, witches, professors banished to Hell, and quite a bit more, and figuring out how to tackle those problems, either to save the world, or sometimes something as small as saving their neighborhood or communities. I think that's a good lesson to go into 2026 with.

Okay, here are the 15 books that I enjoyed the most this year:

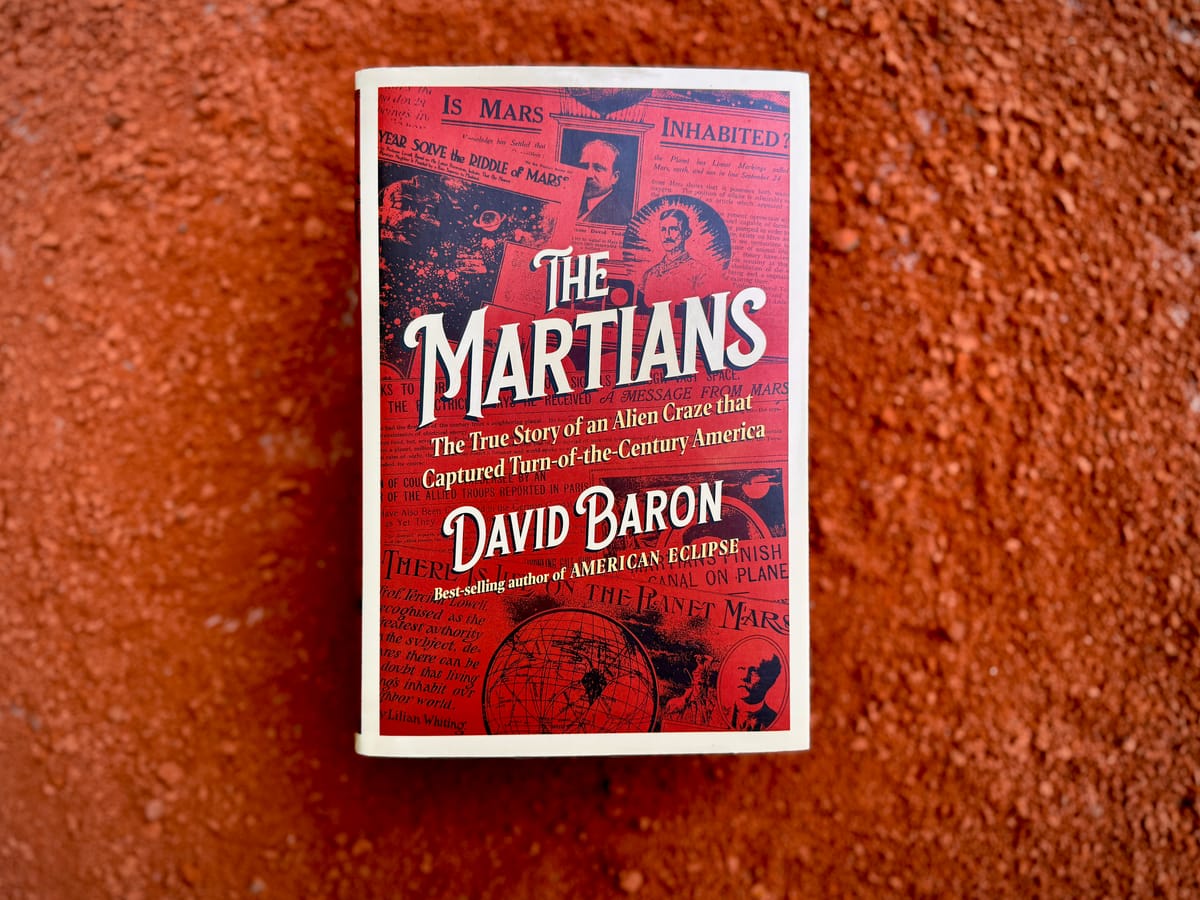

The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America by David Baron

How do we confront the problem of misinformation when people truly believe that they're following the truth? This has become one of the biggest problems that we face these days, but it's not a new phenomenon. In his latest book, David Baron takes a look at the time when a devoted group of academics and adherents believed that Mars was inhabited by intelligent life, and sought to make contacts with its inhabitants.

Baron takes us through the history of science and astronomy and how we observed Mars, and explored the story of Percival Lowell, a Boston-born businessman who became obsessed with the prospect of first contact, even as it became increasingly clear that Mars is as we know it today: a desert devoid of life. It's a striking read that holds plenty of lessons about the assumptions and beliefs that we hold.

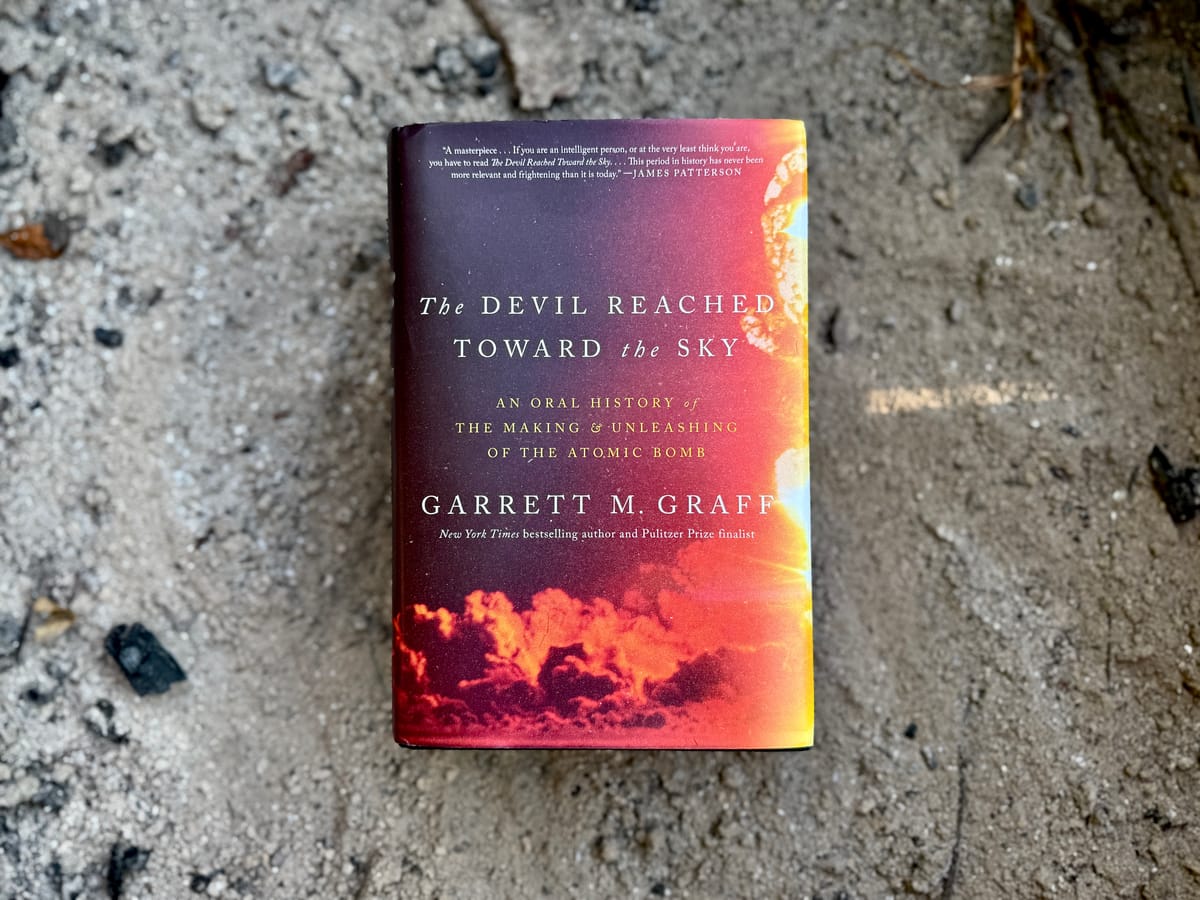

The Devil Reached Toward the Sky: An Oral History of the Making & Unmaking of the Atomic Bomb by Garrett M. Graff

I studied the Cold War in graduate school, and ever since, I've been keenly interested in the story of the atomic bomb and how its development and deployment during the Second World War changed the face of warfare – and the world – forever.

In his latest oral history, Garrett M. Graff takes a look at the month-by-month, day-by-day and even minute-by-minute story of those first terrible weapons, dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki 80 years ago. It's a gripping story about how the United States government undertook this massive, secret program and how all of that work went into developing the first nuclear bombs. It's a story about organization and scientific achievement, but also of doubts, purpose, and consequences.

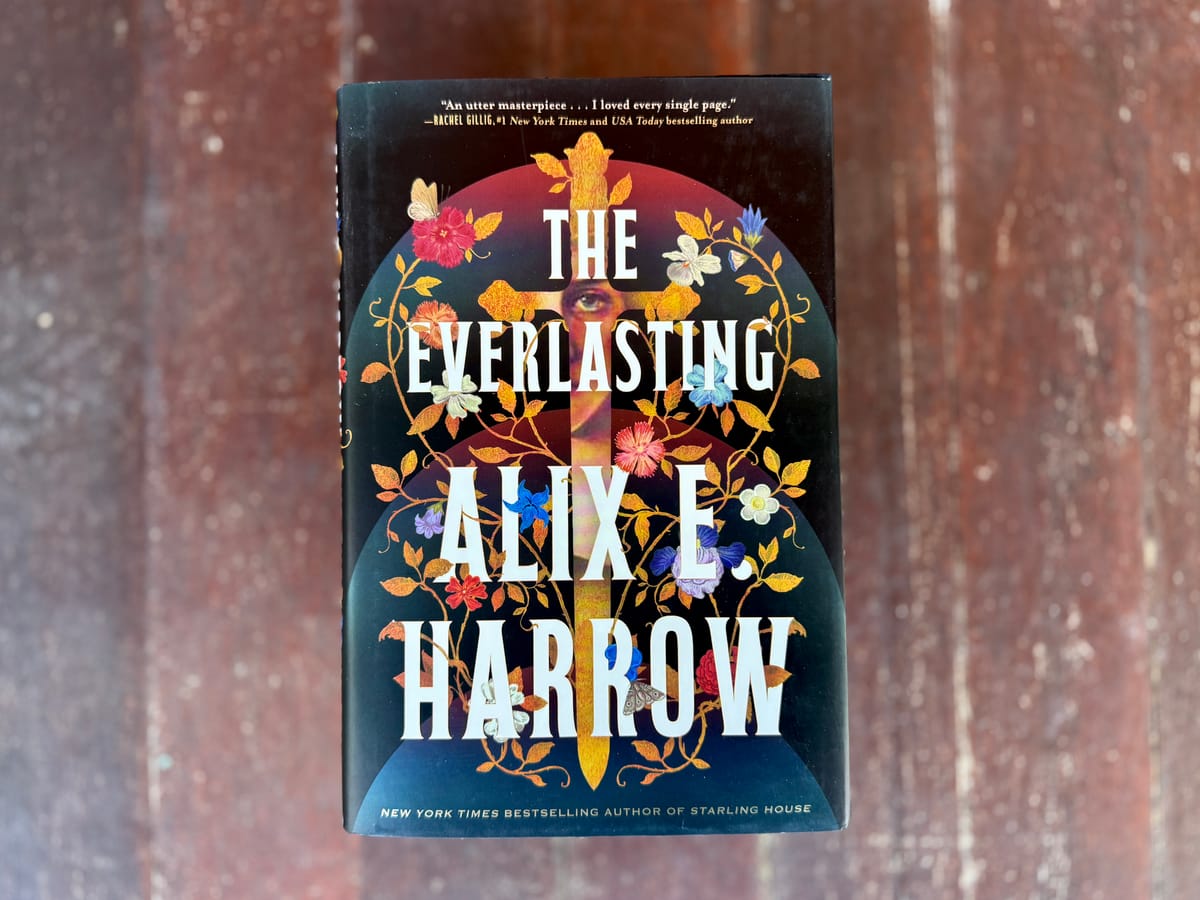

The Everlasting by Alix E. Harrow

Origin stories are often critical to the soul of a country, and the stories and tales of the people closely involved in the founding of one's nation can often be transformed into a form of legend, one that inspires and unites one's citizens. But those stories can also be misused as tools of oppression, as one hapless historian discovers when he's recruited by his government to write the definitive origin story of Dominion, and is promptly sent back in time to observe his country's heroine in person.

As he watches and writes and falls in love with Una Everlasting, he begins to realize that something's terribly wrong; that he's being used to transform Dominion's origin story into something twisted and further away from the character and woman the he falls desperately in love with. It's a powerful read about stories and history, and the distance between truth and legend.

King Sorrow by Joe Hill

When Arthur Oakes and his mother are threatened by drug dealers, he and his friends do the only logical thing: summon an ancient dragon to smite them. That works nicely, but it comes with a complication, said dragon, the titular King Sorrow, now expects them to kill someone each Easter, or one of them will die instead.

The pact kicks off a story that runs for decades, following this band of characters as they work to come to terms with the terrible task before them and the cost that it extracts. This book is a tome, a rich, sprawling epic that explores the consequences of greed, morality, honor, and magic.

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones

An academic comes into the possession of the diary of an ancestor, written in 1912 and hidden away in a wall. As she begins reading and transcribing it, she finds a horrifying story that leads back to the massacre of a group of Blackfeet in the 1800s, and the consequences that rippled out from it.

One of those consequences was the fate of a man named Good Stab, attacked and bitten by a vampire-like creature, he recounts his story to a Lutheran pastor, teasing out a story of revenge, pain, and suffering over decades. It's a terrifying novel, exploring the enduring trauma of the American expansion into the west and how it resonates in the modern day, wrapped up in one of the best depictions of vampires that I've ever read.

Katabasis by R.F. Kuang

How far will you go to get a job recommendation? In R.F. Kuang's Katabasis, Cambridge student Alice Law will go to hell and back. The why is complicated: she accidentally (or maybe not) dispatched her mentor, Professor Jacob Grimes to the underworld, and she hatches a plan to follow and retrieve him in order to ensure that her future in the field is secure. Accompanied by her rival Peter Murdoch, she finds more than she bargained for as Kuang takes us through the various levels of hell as they try and find their late professor.

Along the way, Kuang takes aim at the culture of academia and the way that it can churn students through its halls and abusive relationships, all while exploring the nature of reality, purpose, and existence and what it all means when it all comes to an end.

All That We See or Seem by Ken Liu

When an artist named Elli goes missing, her husband Piers turns to an infamous hacker named Julia Z to try and figure out what happened to her. Elli is a world-famous storyteller who brings audiences together into digital, immersive, shared experiences. Initially reluctant, Julia gets drawn into Elli's work and life, discovering that she had been a client of an international criminal group, and that he might be ransoming her for the information she might have gleaned from their shared dreamspace.

I've long admired Liu's storytelling and his approach to technology and the creative arts, and this novel provides a deft snapshot of the technological world we're hurtling into. In it, he's exploring the nature of storytelling and the digital world, how these tools shape our perceptions of reality and what it means to be an artist in this environment, all wrapped up into a gripping technothriller.

The Bewitching by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

I find that gothic horror is best when it really leans into history, and in her latest, Silvia Moreno-Garcia threads a story of witches across three separate times: 1908, 1934, and 1998. She introduces us to promising young women woman as they contend with a looming supernatural threat, and little do they know, but they're all connected.

Alba contends with a malevolent presence on her Mexican farm, only to find that the danger lurks close to home. Carolyn, Virginia, and Beatrice confront something from their Boston campus in 1934, while Alba's granddaughter Minerva begins studying Beatrice's eventual career as a minor writer and finds that she too has to confront the same dark presence.

That presence are witches who're attracted to the bright potential that these women hold, feeding on their power and using it to their own ends. The result is a novel that examines the cycles of violence that women have faced and is a look at how the powerful go to great lengths to use use manipulation and greed to hold onto power.

Positive Obsession: The Life and Times of Octavia E. Butler by Susana M. Morris

One of the genre's best authors was Octavia E. Butler, who's best known for books like Kindred, Parable of the Sower, Wildseed, and a number of others, books that feel prescient and at times, prophetic. She's the focus of a new biography by Susana M. Morris, who delves into her life alongside the changes that the country underwent between the 1960s and 1980s, and paints a portrait of a woman who was motivated by the politics of the day, and who was determined to reach the goals that she set out for herself.

Butler's vision for the future wasn't so much prophecy, Morris finds: her impoverished upbringing, painfully shy and timid nature led her to becoming a keen observer of humanity and human nature, and wove those observations into her stories. She was someone who was outraged by the injustices of the world, frustrated by the people in power, and channeled that anger into telling stories that sought to address those issues. It's a wonderful portrait of a tragic figure, one who left us far too soon.

Where The Axe is Buried by Ray Nayler

Ray Nayler's novel The Mountain In the Sea was one of my favorite reads of 2023, and he's become one of those authors that I'll seek out whenever he has a new story out. That was the case with his latest, Where the Axe is Buried, which follows a mounting political crisis in a future Europe.

An activist and neuroscientist who escaped from the oppressive Federation (Russia) returns home to visit her dying father only to become ensnared in the country's surveillance apparatus, while an aid to the country's President, is involved in his reincarnation – the latest in a succession of the man's attempts to hold onto power by downloading his mind into successive bodies. At the same time, various European nations have turned over control to AI prime ministers, and one political operative is manipulated into undoing the latches on a potentially catastrophic failsafe that could undo the stability that the continent has enjoyed.

This is a complicated and dense read, but it's an astute look the intersection of politics and technology, and how easily people – and their avatars – can be manipulated into doing things that they wouldn't normally do. It's a book about how institutions function and how easily they can come down if they aren't supported and tended to. It's a read that takes on special resonance amidst the current backdrop of political chaos that we're witnessing around the globe today.

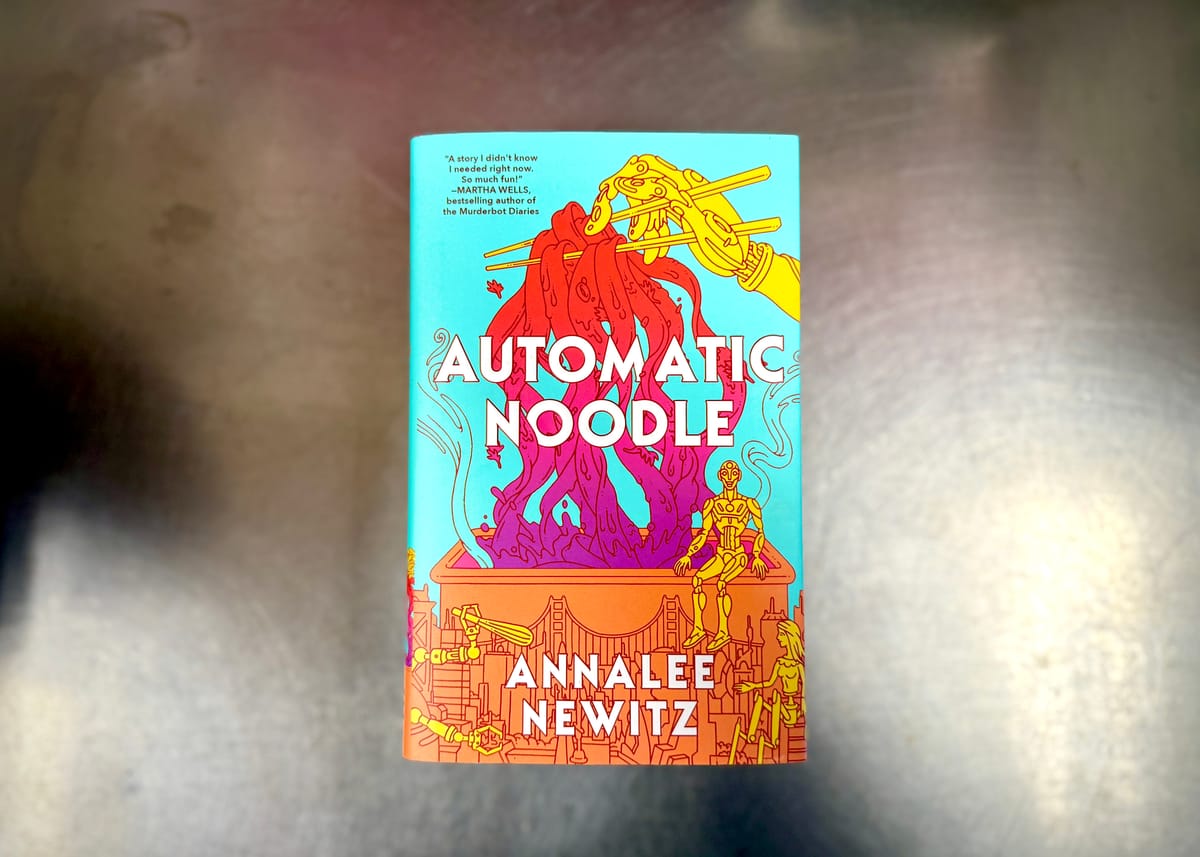

Automatic Noodle by Annalee Newitz

I think a lot about how unity, cooperation, and building bonds with one's neighbors is important in the grander scheme of things: how we hold together as a community, nation, a spacefaring republic, or maybe just a neighborhood. In their latest story, Annalee Newitz brings us the story of a band of robots that are looking to rebuild their neighborhood in a war-torn San Francisco by opening up a noodle shop.

Each of the robots are terrified of being repossessed by their owners after they're reactivated, and they decide to take matters into their own hands. Their goal: try and build a thriving business that their neighbors will like and appreciate, and which goes above and beyond the usual AI-driven ghost kitchens that pop up briefly. In doing so, they build the space for a thriving community, one that could resurrect their neighborhood against malevolent internet users who'd rather trash their online reputation.

It's a cute but powerful story, one that touches on everything from online propaganda to online behavior to dubious ethics of online storefronts and giant conglomerates. It's a read that reminded me that you don't need the high stakes of saving the entire world: sometimes, you just need to plant a seed in a community and give it what it needs to flourish. It's just what we needed in 2025.

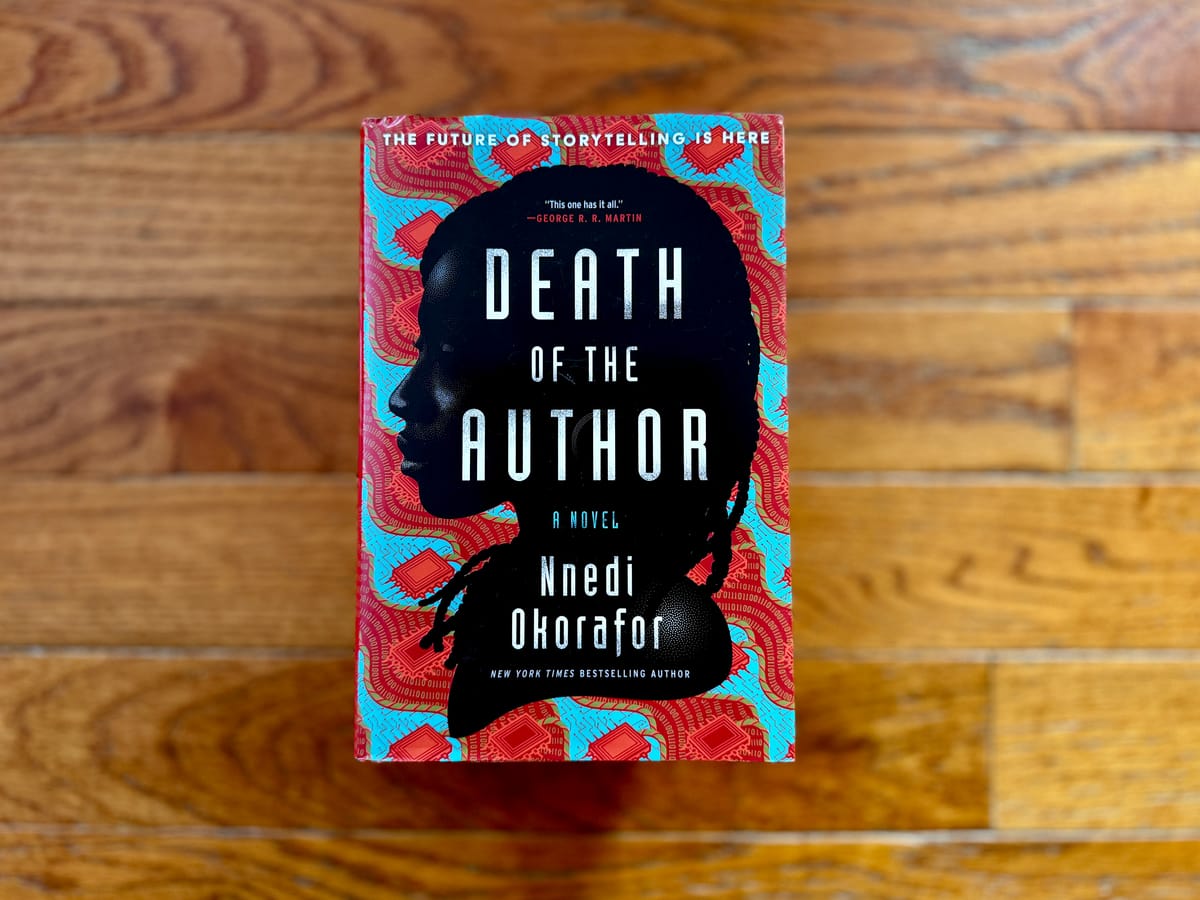

Death of the Author by Nnedi Okorafor

There's a rich tradition of authors penning meta novels about the writing experience, and Nnedi Okorafor's Death of the Author is one of the more interesting ones that I've read, exploring the nature of creativity and storytelling as she plays out the story of a former professor and author named Zelu. After she's fired from a job, Zelu pens a novel about robots, set in a far-future Earth. Inspired, the words flow out of her, and when she eventually shows it to her agent, it goes onto become a massive success: she gets a huge publishing deal and a quick film adaptation, and the pressure is on to continue the story.

Okorafor tells Zelu's story alongside the vibrant science fiction novel that she's writing, Rusted Robots, and we follow her as she comes to terms with her newfound literary stardom and the expectations that come from the fans of the novel.

It's a book that feels as though it's very personal to Okorafor, tackling and exploring the fuzzy intersection of fame and creativity in a world that feels extremely familiar to the minefield of social media and pop culture journalism that we're surrounded by. It's a book about stubbornness, keeping one's eyes on the ball and true to one's creative impulses, even if they take you in places nobody's expecting you to go.

There Is No Antimemetics Division by qntm

How do you fight a war when you can't comprehend the nature of the enemy you're fighting against? That's the premise of qntm's novel There Is No Antimemetics Division, in which Earth is contending with some sort of threat that feeds on memories and intelligence, following an operative from a secretive organization that's working to protect the world, even as they can't always remember who or what they're fighting against.

It's a spectacular novel, one that looks at the nature of intelligence and memory, and how they shape our perceptions of reality and the world. qntm (the pen name for Sam Hughes), tells the story in discrete installments, each one a gripping look into strange, unseen creatures, spy verses spy-style encounters, glimpses of cosmic horrors, and more.

There are times when the world feels unreasonably chaotic and unknowable, and this book feels like an encouragement to move forward and persevere, even if we can't see or conceive of the path before us.

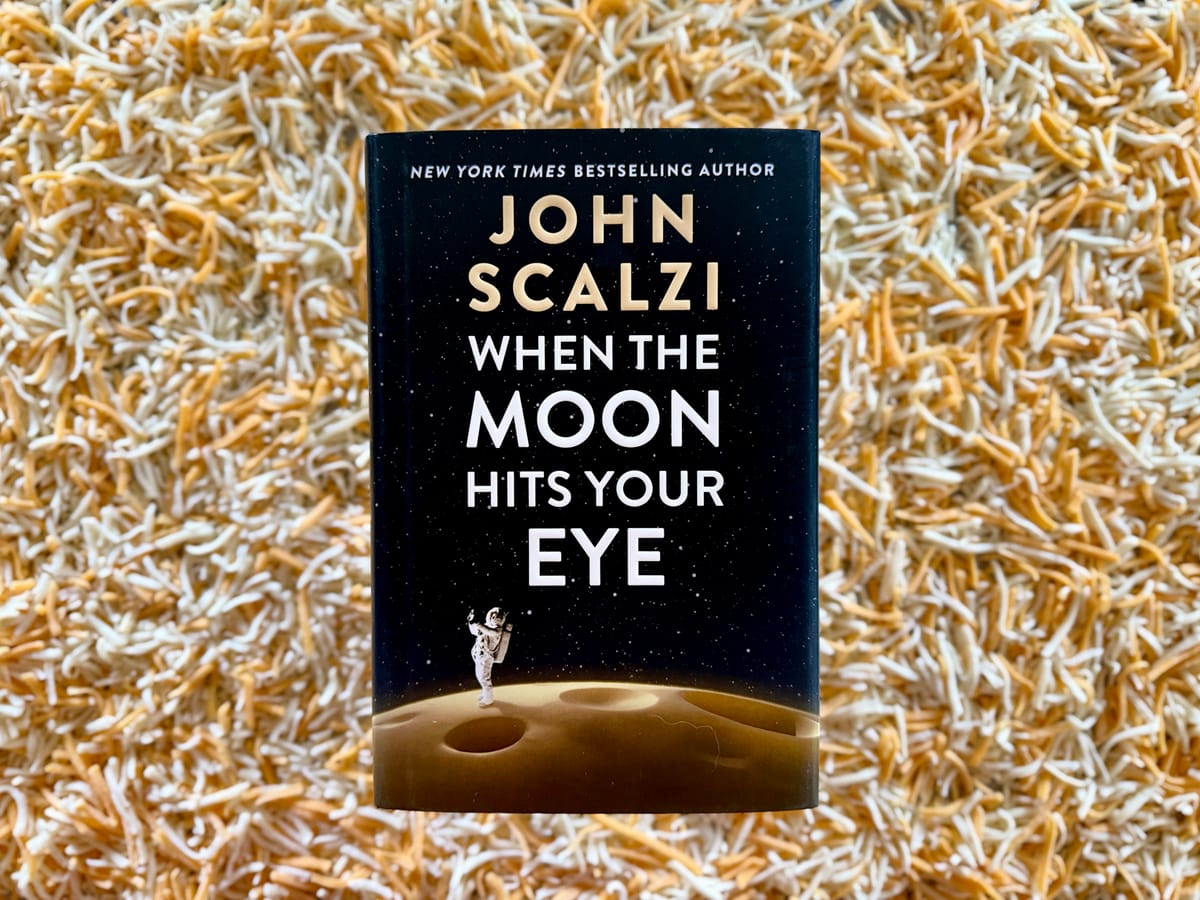

When the Moon Hits Your Eye by John Scalzi

I appreciate a book told in an unconventional way, and when John Scalzi announced that his next book would be about the Moon turning to cheese, that struck plenty of readers as a "yep, he's doing something weird." The resulting book takes this strange phenomenon and plays out in largely standalone installments, one for each day of the lunar month, following people around the country and world as they come to terms with the fact that not only has the Moon turned into some sort of cheese, but it's also coming apart, with apocalyptic consequences for humanity.

What seems like a goofy, light, and somewhat experimental story ended up becoming a fascinating read about how we approach the extraordinary things that we confront in life, like say, a global pandemic, and how we look back on these types of events with fading and imprecise memories of what actually happened, even as we lived through them.

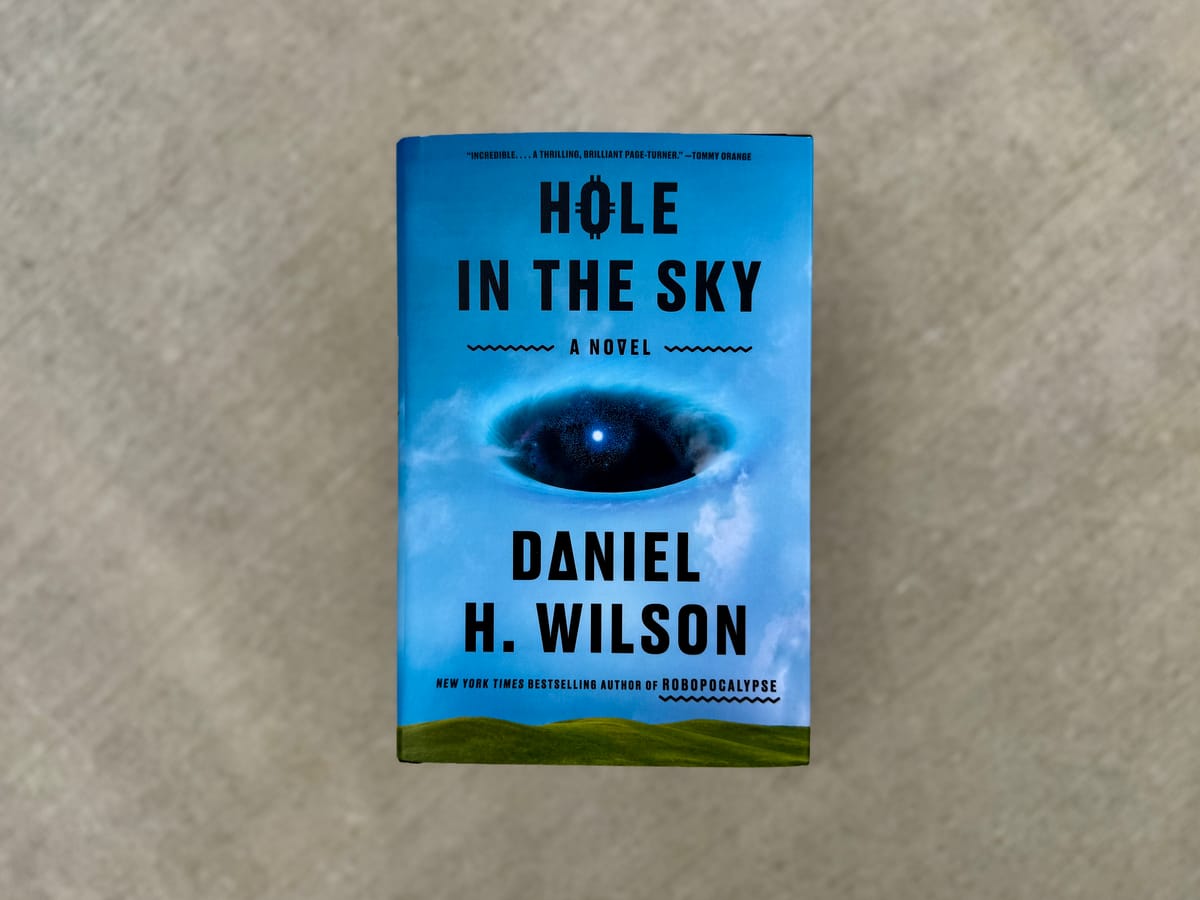

Hole In the Sky by Daniel H. Wilson

What does an alien invasion look like if your own people's past has confronted alien invasions? That's the question at the heart of Daniel H. Wilson's latest novel, in which he plays out an otherworldly encounter through the eyes of four characters: an unnamed man watching a prophetic machine, a worn-down oil worker, a NASA mathematician, and a military specialist who studies UAPs.

As all parties converge at the Spiro Mound complex in Oklahoma, Wilson shows that first contact isn't always a "take me to your leader" situation, and how we view intelligence and intention might be very, very wrong. In doing so, he prompts the reader to consider that what we think we know about the world, through the lens of science and cosmology, could be two sides of the same coin, and that we should be ready to assume nothing when it comes to the unknown.

These were my favorite reads of 2025, and as a reader, it was a very good year.

What books resonated with you? Let me know in the comments.