Origin stories

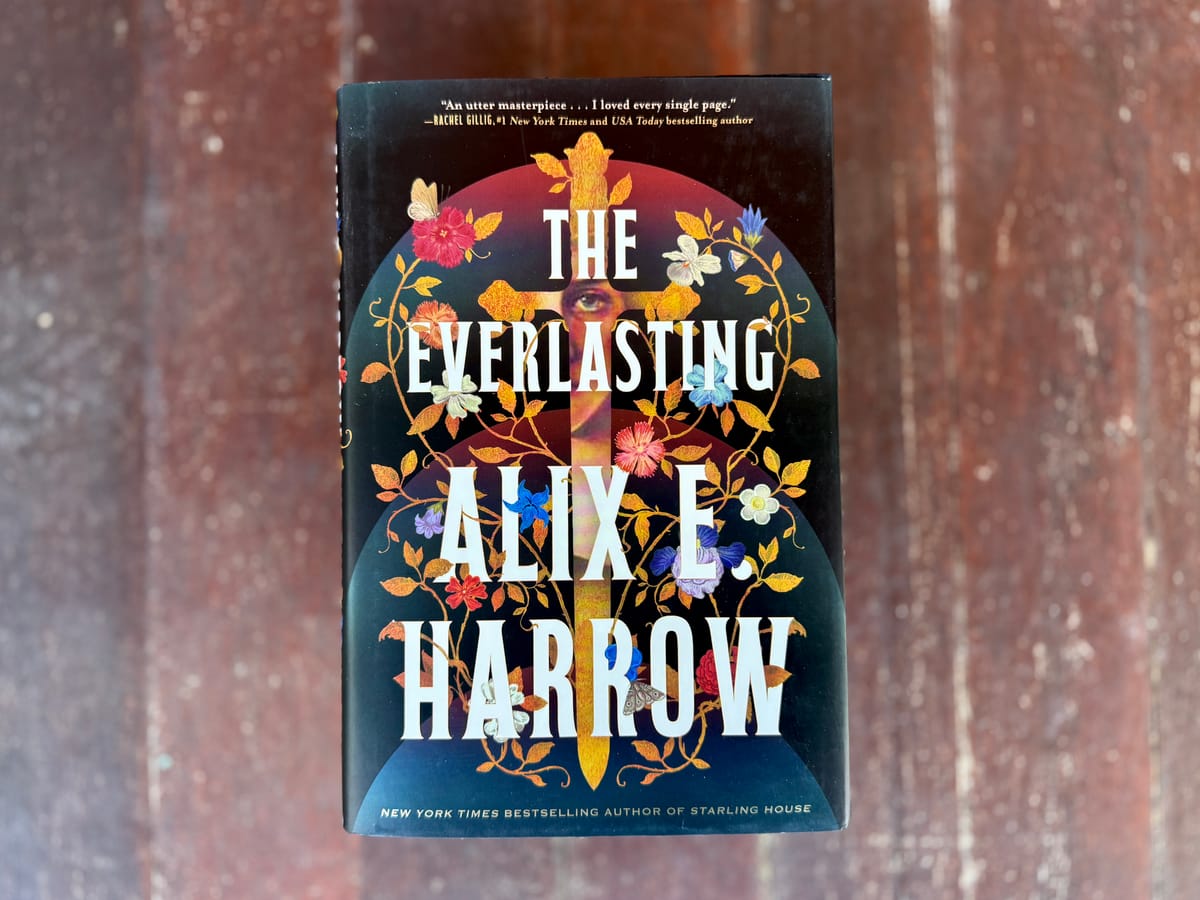

Alix E. Harrow's The Everlasting is a powerful book about a nation's origin story and how such narratives can be manipulated

Something that I like to tell students about history is that it's a field that's all about storytelling. As historians, we're often tasked with interpreting the past based on whatever sources we can find – everything from contemporaneous sources such as letters, diary entries or other relevant documents, to second-hand accounts and memories, to to physical evidence such as archeological findings or artifacts from a person's life or notable event.

But what if you could go back in time to study a person or event? Time travel is one of those tropes that brings out endless thought experiments about what someone might find, with books such as Connie Willis's Oxford Time Travel series or Michael Crichton's Timeline seeing historians jetting back to the past to try and see for themselves how things played out. In her latest novel, The Everlasting, Alix E. Harrow puts a slightly different spin on studying the past: what if you could go back to the origins of one's nation and nudge the story a bit to prop up a legendary heroine whose tragic death marked the starting point? And what happens when the historian you send back in time ends up falling in love with said heroine?

The result is a powerful book that tackles the idea of a nation's founding and the narratives that lie at the center of its consciousness. It's an exploration of the power that storytelling holds for one's nation, and the pitfalls that occur when these narratives are weaponized.

The nation of Dominion was founded centuries ago, thanks to a brave orphaned girl named Una who takes up a sword from a yew tree and embarks on a series of quests in the service of Queen Yvanne before she's betrayed and murdered by a rival knight.

Fast forward a number of centuries and Dominion is still around: it's become a powerful nation that's been waging a series of offensive wars against its neighbors, in which one patriotic soldier, Owen Mallory, fought before entering academia as a historian. He's the odd one out from his peers. He's mixed-race, the product of what he believes was a short-lived romance between his father on campaign and a local in a war zone, and while he's a steadfast believer in Dominion, they're political radicals, critical of the wars that the country is waging and the tyrannical direction it's headed.

When a mysterious package arrives on his doorstep, he discovers that it's an impossible manuscript: a first-hand account of the story of Una. Shortly after its arrival, he's summoned to the office of Dominion's Minister of War, Vivian Rolfe, who tells him that it was a loyalty test that he passed. His task isn't to translate the book, but to write it.

He soon finds himself face to face deep in the past with this legendary figure. Una Everlasting has been tasked with one final quest to recover a grail from the country's last dragon, and after a bit of convincing, he accompanies her, learning about the stories that have sprung up around her at the time, and following in her literal footsteps to see how this national origin story actually played out.

What he finds isn't exactly what he expected:

"They had shied from the sheer scale of you, narrowing the great sweep of your shoulders, tapering your wrists and waist. They had made your face smooth and poreless, forever youthful, when in truth it was pocked and wind-burnt, with heavy lines carved between the brows. Your hair was not the sulfuric yellow of a Saint of Dominion, but the stark white of a snapped bone. A thick welt of scar fell through your left brow and into the eye beneath it, so that the pupil was misshapen, elongated into a black tear."

Myths are an interesting thing: they're stories that smooth out the past for those in the present, sanding down what once might have been true into a useful tool. In college, I had one influential professor who pointed out that the men who participated in the Boston Tea Party and who were writing pamphlets and agitating for change weren't just ordinary folks who were frustrated – they were political radicals, with views far outside of the norm at the time. They were complicated figures who lived rich human lives, and who would probably not recognize the lionized versions we imagined them to be.

This is what Owen discovers when he's abruptly shunted back in time: Una isn't the beautiful, noble figure he had grown up learning about. She was complicated, exhausted, and had lived an incredibly difficult life up to that point. The quests and missions that she had undertaken fell far short of the ones that had been written into legend. In one notable passage, she muses that the queen had sent her off to fight dragons not because they were horrific, evil beasts – indeed, Harrow depicts them as rather pathetic creatures – but because they were a useful as a common threat that the queen could rally her people behind.

Harrow has written the The Everlasting at an interesting time: in 2026, the United States will celebrate the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the moment of origin for the nation. It, and the American Revolution which surrounded it, have become almost mythic in statue in the minds of the American public. It's a rousing origin story: a band of idealistic figures stand up and defend themselves and their countrymen against the malevolent British Empire, ultimately earning their independence as their own nation, eventually becoming the prosperous nation that affords its citizens with life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness today.

Any student of history will point out that as origin stories go, the truth is far more complicated and nuanced: the founding fathers were amongst the nation's wealthiest individuals (in no small part because they were slaveowners), that the buildup to revolution wasn't quite as clear-cut as it appears looking backwards, and that the very idea of rising up against Great Britain was a divisive and controversial act that wasn't universally shared amongst the American colonists.

But origin stories are powerful things, and you don't have to look far for people who're downright hostile to any ideas that run counter to the mythologies that we internalized at school: just look at the right-wing freakout over the way Ken Burns presented the conflict in his recent series The American Revolution, or to online spaces where any type of history is being discussed.

As a historian, Owen is provided an opportunity of a lifetime: set the record straight by going back and time to try and find the true story of Una Everlasting, by observing her life and actions and documenting them. But historic truth and building a national figurehead are two very different things, especially when it comes to governance and politics. In an ideal world, these two things will overlap, but in Dominion, Vivian Rolfe has other plans. It takes some time and distance for Owen to recognize the dire state of his adopted homeland: it's on its way to becoming a fascist state, and when he meets Rolfe for the first time, she talks about her desire to lock up protesters and that they've reached a crossroads:

"Finally, after centuries of strife, we stand as Yvanne imagined us: a nation united, at peace. But peace is a fragile, fleeting thing. It must be protected, fought for, defended against all threats, native and foreign alike– and I fear we've grown weak."

The cause, she points out, is more dissent in the country, ewer people in churches and young people who've lost their direction. "We've forgotten– as a nation, as a people – who we are."

Rolfe's motives aren't out of a desire to construct or unearth a historical record; but to weave a new one, sending a storyteller back in time to nudge the narrative in ways that are favorable towards the creation of the state that she so desperately wants to see.

As a trope, time travel offers endless opportunities for thought experiments: what is the impact if you change something big (or innocuous) in the past? Ray Bradbury's short story "The Sound of Thunder" best described such a ripple effect when a time traveler accidentally steps on a butterfly, ultimately changing his future in an unexpected way. While plenty of time traveling stories have dealt with the unintended consequences, and where there's accidents, there can also be intention, as people realize that they can manipulate the past towards their own ends, as in Annalee Newitz's The Future of Another Timeline, in which a woman finds herself fighting against people looking to shape the past to control the lives of women in the present.

Harrow's Rolfe doesn't quite have those specific goals in mind, but the world that she wants to establish is straight from the fascist 101 playbook. She recognizes that the stories we tell about ourselves are critical to controlling one's perceptions of the past, and by tinkering with the underlying source material, one can cement an ideology that's so ingrained in one's culture and history that it'll be all but impossible to mount any sort of opposition or counternarrative.

This is why Harrow's book strikes such a chord. We're living in a time when the country is broadly cracking down on education and history, and where the president speaks openly about his desire to reshape how museums and historical organizations present the past to the American people. Tools and actions such as widespread book banning, the organized harassment of academics, and other academic challenges seek to reinforce a mythological view of the past, one where our founders were above reproach, and where the country's real and persistent problems are swept under the rug, leaving its citizens festering in systemic inequalities.

Fortunately for Dominion, Owen doesn't remain a spineless academic for long, and as he travels back to the past over and over, he continually recognizes that the vision that Rolfe seeks to establish for the country is out of step with reality, even with the tweaks to the timeline that he's been helping to establish. The truth is often complicated, immutable, and stubborn: it's borne out of the character and actions of the people who make it, and even when we try and mold it to our liking. As Owen and Una fall in love over and over again, its these qualities and character that resists being tampered with, ultimately delivering a better world far in the future. Hopefully, our own timeline and understanding of the past will be just as stubborn.