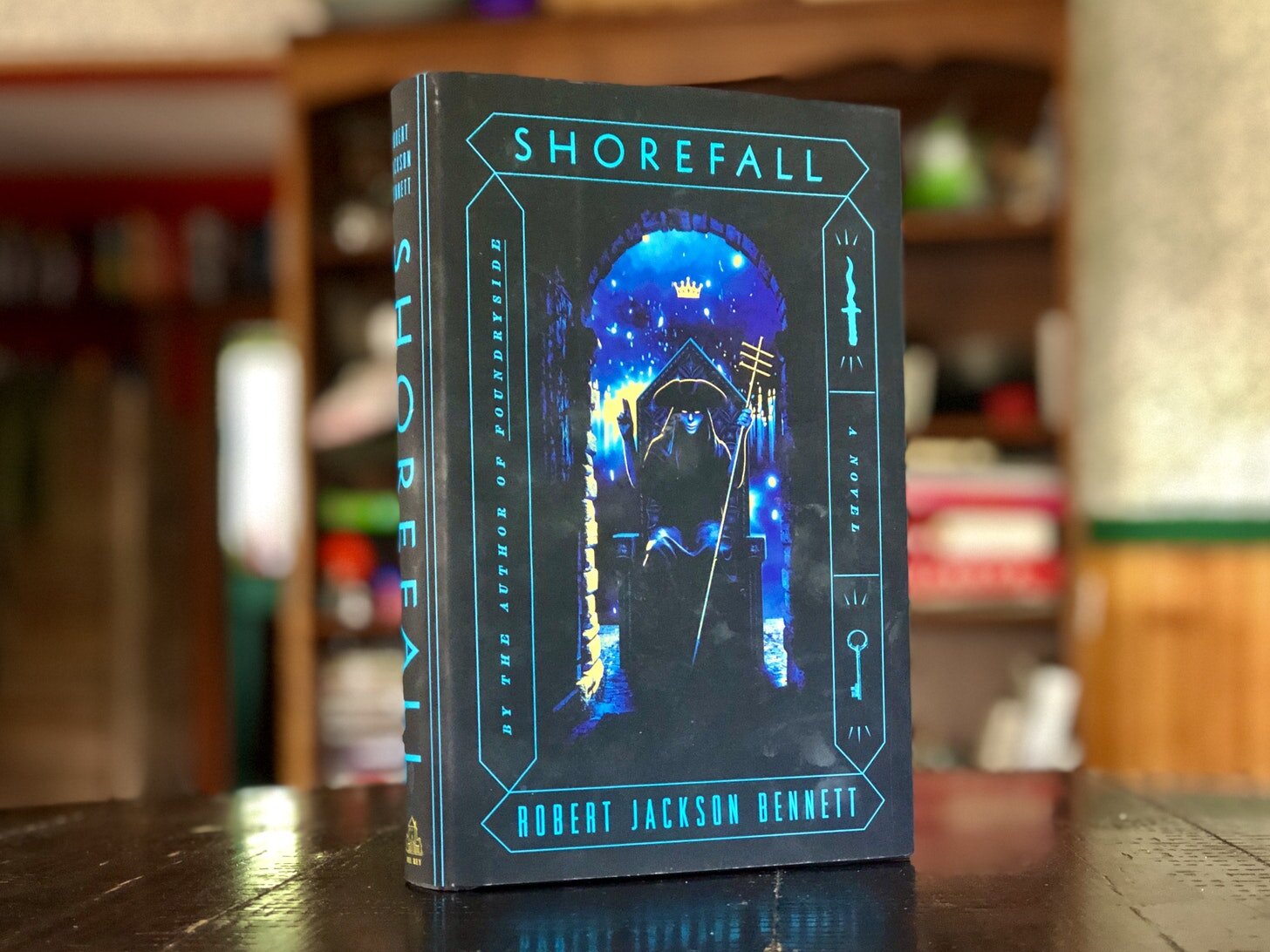

Robert Jackson Bennett’s Shorefall

/Two years ago, I picked up Robert Jackson Bennett’s Foundryside, and was blown away by his depiction of magic. In my review, I wrote about the book as a cyberpunk-like novel, about a young thief who picks up a magical key and gets pulled into a conspiracy on the part of some shady people to reprogram reality.

Bennett approaches magic like it’s a technology: it’s a force that permeates the world, and with the right arguments, you can convince an object to do something that it might not do. Say for example, you want to secure a door. Here in the real world, you might put a lock on it, with a key that allows you (or anyone with it) access. In Bennett’s world, you enchant — scrive — the door, and it knows that it can only open the door under certain circumstances: someone puts the right key in the lock, or it’s enchanted to recognize a specific person or heartbeat, or something like that. To get in, you need the right person or key, or in Sancia Grado’s case, you have the ability to talk directly to the enchanted door, and convince it that it’s not breaking its programming if it would only open in the other direction.

Her particular set of abilities here made her an ideal thief, and we learned in Foundryside that she was a former slave who had been augmented with a scrived plate that gives her this ability. After discovering a key named Clef, she stumbles upon a plot from some a very shady person that want to use Clef to rewrite reality to suit their needs by transforming themselves into a god.

Shorefall takes place a couple of years later, and Sancia and her friends have been working to remake the world in their own ways: they’ve been trying to dismantle the established merchant houses that have an iron-clad grip on her world’s economy, which leads to slums, slavery, and oppression. This work comes to a screeching halt when a character named Valeria reaches out to Sancia with a message: her creator, an ancient hierophant named Crasedes Magnus — a godlike character that had destroyed entire civilizations over his reign — has somehow returned to life, and he’s aiming to remake humanity.

There’s a lot going on in these two books, but one thing really jumped out at me: power corrupts, even when someone has the best of intentions. Much of the novel covers Sancia and her allies working to figure out the threat to the world, working out how to address it, and then trying to prevent the worst case scenario.

There’s plenty of fantastic horror here: Sancia and company trying to stop Crasedes Magnus from entering the city of Tavanne, only to discover that he’s figured out how to not only return to life as a living god (there are some real Lovecraftian elements to him here), but he’s pretty much put together a bullet-proof plan to enact his plan: essentially reprogram humanity, stripping people of free will. Over his millennias-long life, he’s seen humanity rise and fall a couple of times, and he’s realized that our inherent ability to improvise and innovate are traits that are inevitably weaponized, leading to war, concentrations of wealth, and slavery. Remove that ability, and humanity would exist peacefully. Earlier, he created Valeria as a tool to help with this process: designing her to eventually reprogram humanity before she rebelled and snuffed him out.

There’s elements of Crasedes Magnus’s plan that feels very much like something out of a supervillan playbook: have grievance with the world, create master plan, profit??? And while that borders a bit on the cliche side of things, Bennett does a masterful job of playing up Crasedes Magnus as a horrifying and yet sympathetic character. We learn that he has a deep relationship with Clef, and that their own personal origin story sets up his motivations in a fairly logical manner. The thing here is — and this is where the best villains are made — he’s not entirely wrong about what he wants to accomplish. Technology certainly leads to inequality (just look around at the present state of the world or hell, even the 20th century) and oppression around the world, and there are points where drastic action is required to enact change.

We see both sides of the coin here: Sancia and friends getting information from a would-be ally who’s trying to dismantle the system that led to their respective enslavements, and Crasedes Magnus, who might have understandable motivations, but who has become so corrupted by his own power that any system that he puts into place will be just as bad as what he’s trying to replace — or worse. It’s a solid setup for the final installment of the series, and I’ll be interested in seeing how this ends up.