Kingdom come

How George R.R. Martin and Game of Thrones took over popular culture

There’s a story that George R.R. Martin has often recounted about his level of fame. Shortly after he published A Game of Thrones in 1996, he went on a book tour, where at one of the stops, he found he wasn't the only notable guest. When he arrived at the Barnes and Noble in Texas, he was greeted with a crowded parking lot, and went in, thinking that it was a good sign for the book: “Boy, this book is big. Look at all these people coming in.”

They weren't there for him: he was competing with Clifford the Big Red Dog, and the hundreds of people who had showed up at the store were for the character, while only a couple were there to see him.

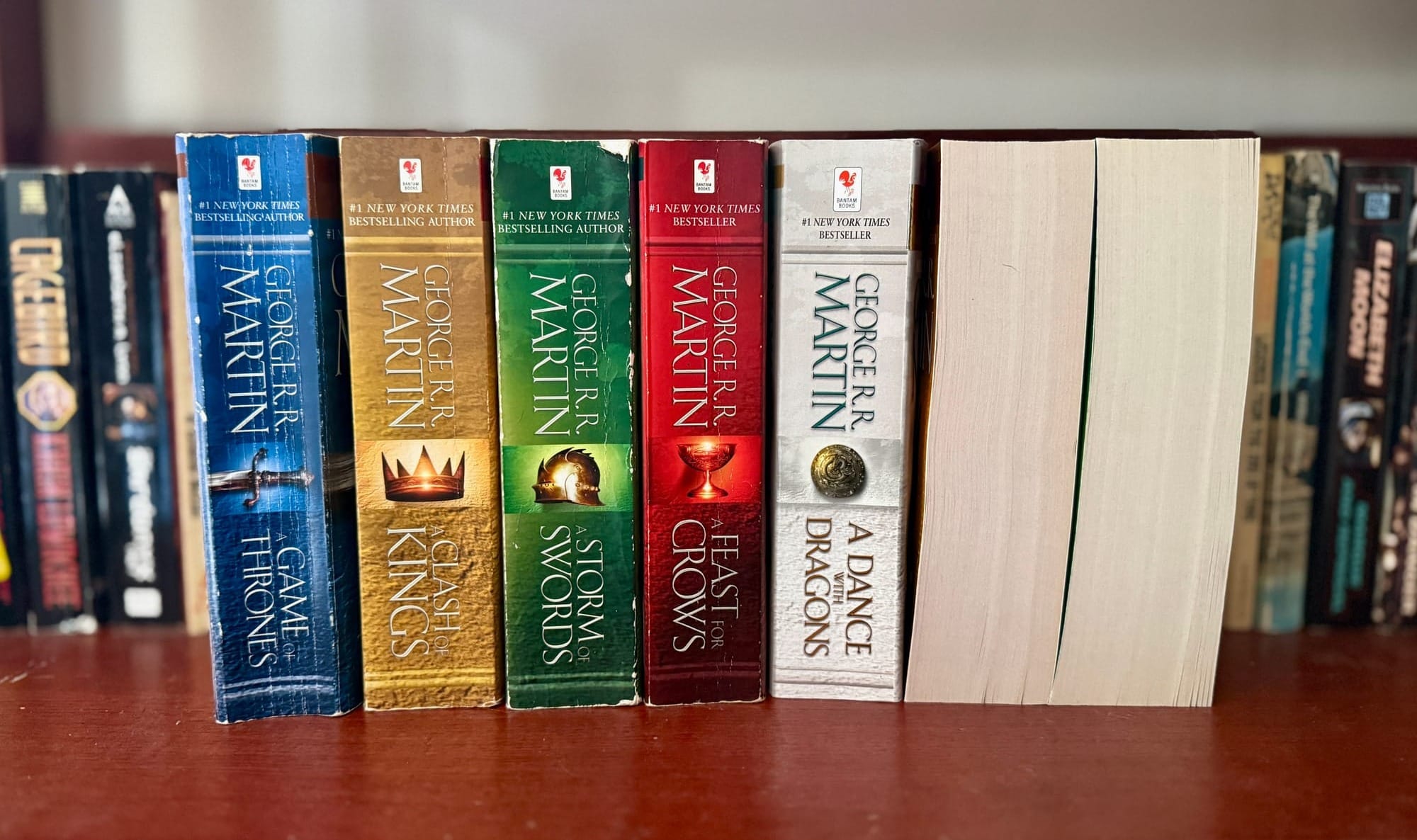

Three decades later, this sort of reception is unimaginable. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire — as of yet unfinished — has morphed from a niche epic fantasy into a popular culture juggernaut, with five bestselling novels, blockbuster author events that command thousands of passionate readers, a trio of big-budget adaptations, and enough name recognition that if you stop anyone on the street and ask what they might know of the author, they’ll likely know that he's long overdue on the series’ next installment, The Winds of Winter.

A series of grim, dense, and morally complicated fantasy novels, A Song of Ice and Fire has been the most unlikely of publishing success stories, and is the latest chapter in an already unlikely career. It's also a series that's followed the dramatic changes in the publishing industry, the motion picture industry and rise of streaming, and the changes that have come with popular culture and fandom.

40 years to an overnight success

George R.R. Martin wasn't destined for success. Born on September 20th, 1948, he grew up in Bayonne, New Jersey, the son of a longshoreman and housewife who had fallen on harder times. He described his hometown as an insular, working class community – "a city unto itself ... a world unto itself, really," and that his early childhood was a lonely one: "I wonder whether imagination isn’t born of need as well. I had to make up stories and adventures. If I hadn’t, it would have been very lonely in that backyard, with just me and my sticks. I had no friends or playmates."

He eventually found peers when he and his family moved into a series of newly-built public housing projects, and they became an outlet for his vivid imagination, sometimes charging them for each story. Along the way, he began spending his allowance on cheap paperbacks and comics, eventually writing a fan letter to Marvel Comics, which introduced him to the world of comics fandom and fanzines. When he was in middle school, he discovered J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, which "blew my mind."

Martin eventually left Bayonne to study journalism at Northwestern University in Illinois, but he never strayed far from his interests in science fiction and fantasy, eventually publishing 'The Hero,' his first story in Galaxy Science Fiction in February 1971. It was the start to a notable career as a science fiction author. Within a couple of years, and numerous stories later, he was attracting the attention from colleagues and readers across the field: he was a finalist for the 1973 John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer (now the Astounding Award), and picked up his first nomination for a Hugo award for 'With Morning Comes Mistfall' in 1973, and a win for his novella 'A Song for Lya' in 1975, the first of a steady stream of award placements and wins over the course of the decade, thanks to stories such as 'Nightflyers,' 'Sandkings,' and others.

Writing in Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction, author and genre historian Brian Aldiss characterized Martin's as "a romantic whose ideas and imagery spanned a wide and colourful spectrum. Vampires and spacecraft sit cheek by jowl in his stories," and that his defining trait was to "imbue the expected magazine formulae—romantic, often sentimental and mechanistic—with a degree of realism.”

He also began writing novels during this period, first serializing After the Festival in Analog Magazine starting in in April 1977 before publishing it as Dying of the Light later that year, Windhaven (co-written with Lisa Tuttle) in 1981, Fevre Dream in 1982, and The Armageddon Rag in 1983.

Upon its release, The Armageddon Rag halted the momentum of Martin's career. Fevre Dream brought his career to new heights, and his next was his most experimental and was "supposed to be a gigantic bestseller; they paid me a lot of money for it" only for nobody to buy it. It was "a total commercial disaster," he later told Publishers' Weekly in 2005. "Instead of taking me to the next level, it almost destroyed my career."

The failure prompted Martin to take a break from life as a novelist, but there was a silver lining: producer Philip DeGuere had optioned The Armageddon Rag with the intent of making a film. The film never materialized, but following the success of his series Simon and Simon, DeGuere was given the chance to reboot The Twilight Zone, and hired Martin as a staff writer for the series.

Thus began the next phase of Martin's career: as a screenwriter. He adapted his novella Nightflyers in 1987, and worked on a variety of shows, including Max Headroom and Beauty and the Beast. He also maintained some connections to the SF community: he began work on a shared-universe project called Wild Cards, set in the post war period as humanity contends with the arrival of an alien virus that imparts people with superpowers.

By this point, Martin was becoming disillusioned with Hollywood. His pitches and drafts were going nowhere, and as he recounted to The New Yorker's Laura Miller in 2011, his vision often outstripped the capabilities of television. As one producer told him "You can have horses or you can have Stonehenge. But you can’t have horses and Stonehenge."

He decided to go back to that first love: books, where he wouldn't have to worry about the constraints from producers. "I’m sick of this," he recalled to Jennifer Armstrong of Entertainment Weekly, "I’m going to write something that’s as big as I want it to be, and it’s going to have a cast of characters that go into the thousands, and I’m going to have huge castles, and battles, and dragons."

When I started Transfer Orbit back in 2018, I wanted to use it as a place to write about genre topics and news in ways that I loved reading: a ton of niche detail and explore the complexity and depth of a story, regardless of how long it takes to tell it.

That's the case with this story: it's long and involved, and 'm pleased with how it's come together. I learned a lot researching and writing it, and I hope that you will as well.

This newsletter is free to read, but it does take resources to write. I've spent the last week taking on long evenings diving into decades-old interviews, chat transcripts, reviews, and pouring through reference books to put this story together. And that's before I went about proof-reading, editing, gathering up books to photograph (rather than rely on stock images). If you enjoyed reading this and want to see more pieces like it, please consider signing up as a TO supporter.

Fantasy ascendant

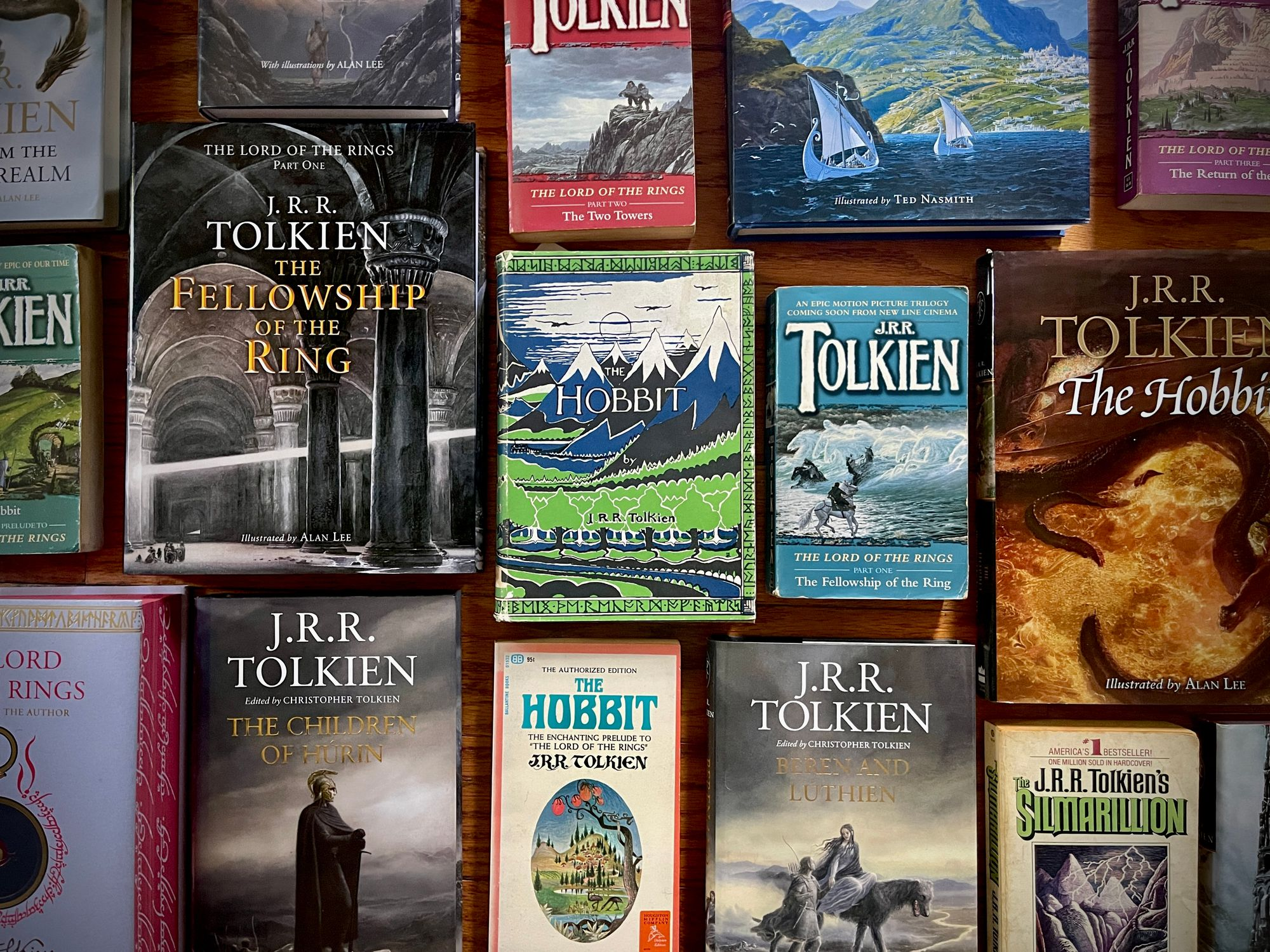

Fantasy's roots stretch back to antiquity, but for the modern state of the genre, J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings helped set the stage for the field we know today. Initially released in the United Kingdom, it found a small and captive audience before making its way to the United States thanks to a copyright loophole. The resulting back and forth between Tolkien and Ace Books and subsequent "authorized" edition from Ballantine helped prime the trilogy to explode in the 1960s, where it found a ready and eager population of readers in the counter-culture movement.

The result utterly transformed the genre world as publishing houses worked to find their own versions of Tolkien's masterpiece. In 1969, Ballantine Books launched an imprint devoted to republishing the genre's classics, such as from Lord Dunsany, William Morris, George MacDonald, Clark Ashton Smith, and H.P. Lovecraft, and many others, while other authors such as Fritz Leiber, Michael Moorcock, and Ursula K. Le Guin found new audiences for their fantastic worlds and characters.

Writing in Fantasy: A Short History, Adam Roberts notes that "through the 1970 the popular success of Tolkien in the 1960s was consolidated via a considerable number of new fantasy works written in more-or-less straight imitation of Lord of the Rings," and that as readers began looking around for other stories, there was a boom in new imitators. "1970s authors also began writing new-minted Tolkienian fantasy of various kinds, and various quality – though few of these exercises in pastiche Tolkieniana have any real merit – and some where very successful in commercial terms." Authors such as Terry Brooks, Stephen Donaldson, and Roger Zelazny etched out durable and long-lived careers penning high fantasy series.

Roberts notes that while there were many imitations of Tolkien's stories, they were also popular with readers. "This mismatch in success and quality is in itself interestingly indicative of a wider cultural logic, but it has a particular valence for fantasy: readers chasing 'enchantment' in amongst increasingly reified and repetitive-iterative copies of copies."

It's in this environment in which Martin found himself while trying to figure out how to move on from Hollywood. In 1991, he began writing a new science fiction novel set in his larger "Thousand Worlds" universe, Avalon. He didn't make it far. A new idea came to him: the scene where the Starks discover a dead direwolf, with a litter of starving puppies. "When I began, I didn’t know what the hell I had," he told Alison Flood of The Guardian. "I started exploring these families and the world started coming alive. It was all there in my head, I couldn’t not write it. So it wasn’t an entirely rational decision, but writers aren’t entirely rational creatures.”

This was something altogether different for the writer, who built his career as a science fiction author. Martin makes an appearance in Patti Perret's 1984 photography book The Faces of Science Fiction: Intimate Portrait of the Men and Women who Shape the Way We Look at the Future, in which he mused about how not all of his books fit the SF label perfectly. "So maybe I have to plead guilty to being a writer first and an sf writer second. Still, if they want me to get out of this field, they'll have to drag me out bodily, kicking and screaming... I'm an sf person, and always will be."

Seven years later, and he was contemplating something very different. "Tolkien had an enormous influence on me," he told Flood, "but after Tolkien there was a dark period in the history of epic fantasy where there were a lot of Tolkien imitations coming out that were terrible [and] I didn’t necessarily want to be associated with those books, which just seemed to me to be imitating the worst things of Tolkien and not capturing any of the great things."

He set Avalon aside and began working on this new project. As he wrote, he began building out the world. He drew up a map, started charting family trees, and soon realized that this was much larger than a shorter story. "I didn't even know whether it was a novel or a novella or something at first," he told io9's Charlie Jane Anders, "By the summer of '91, you know, it just came to me out of nowhere, and I started writing it and following where it led. But by the end of that summer I knew I had a big series."

Hollywood wasn't quite in the rearview mirror, and he still had some irons in the fire: a concept of a science fiction television show called Doorways, about parallel worlds. He was able to successfully pitch the show to earn a pilot order, which went into production in the spring of 1992. While ABC liked the series enough to order a handful of additional scripts, the network didn't end up picking it up. (IDW would eventually adapt the series as a comic book in 2010.) Martin wrote pilots for another couple of shows, but ended up returning to the fantasy story that he set aside to work on the show.

He showed his agent what he'd come up with, and provided a broad outline for what would follow: the first novel, A Game of Thrones, would be followed by two additional books: A Dance With Dragons and The Winds of Winter. But by the end of 1995, he'd written more than 1,500 pages and told Anders that he "wasn't anywhere close to the end of the first book," and that he determined that he would have to split that first novel into two.

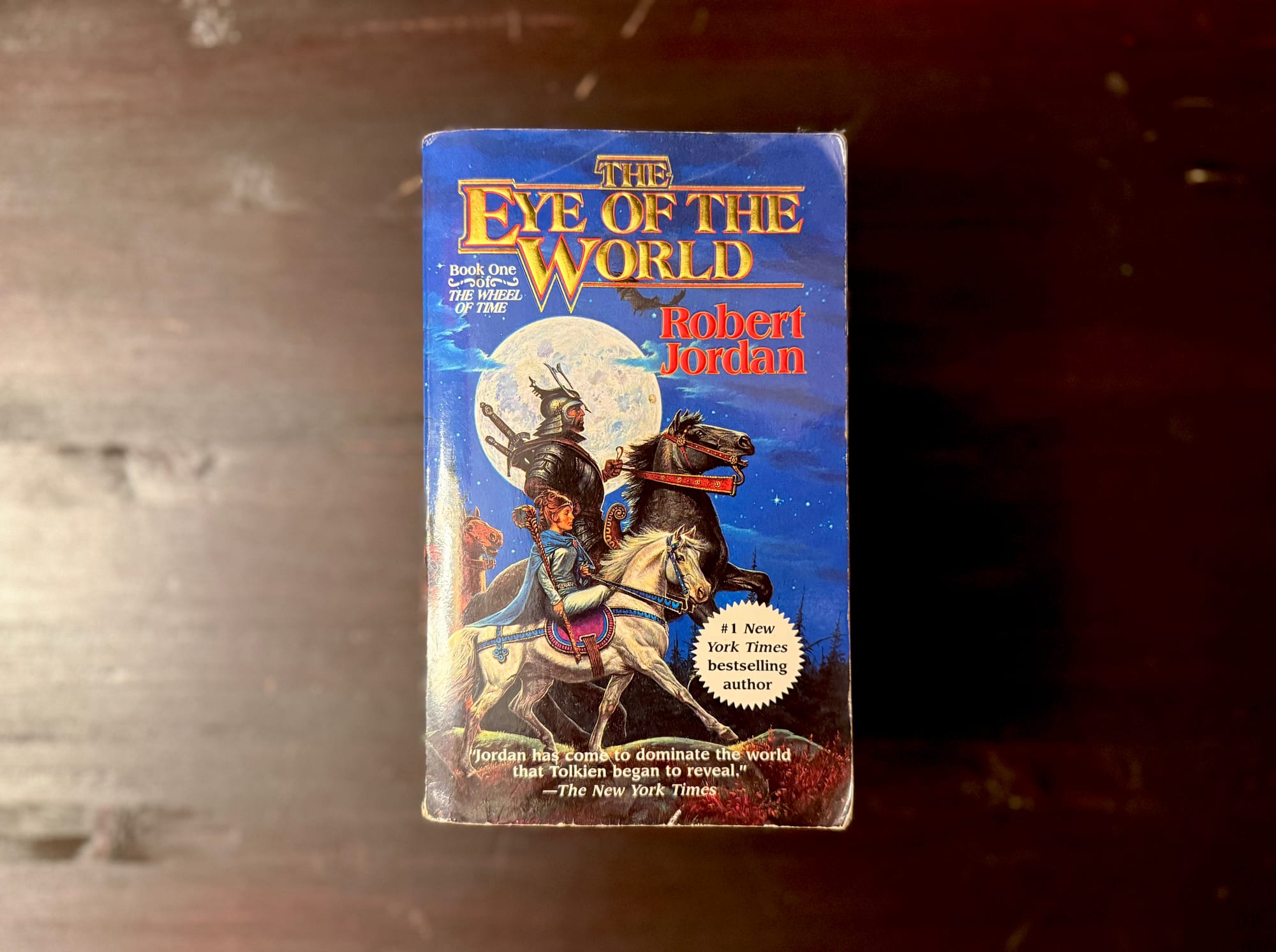

There was precedence for this in the publishing world. In 1990, author Robert Jordan, who began writing fantasy in the 1980s (notably a run of seven Conan the Barbarian novels in three years), released the first installment of a new fantasy epic series called The Wheel of Time, The Eye of the World, in February 1990.

Like many of his predecessors, Jordan was loosely inspired by Tolkien's epic, down to its trilogy structure. His publisher, Tor Books, was enthusiastic for it, and took a number of steps to prime it for success: "We did it in trade paper because we were afraid we couldn’t get enough out of a fat hardcover book," publisher Tom Doherty recalled. "Trade paper wasn’t anywhere near as big then as it is now, but we thought that’s good, too, because it will call attention to itself. It’ll be different. So we did it in trade paper and sold 40,000 copies, which was huge for trade paper in those days, for the first of a fantasy series."

It worked: The Eye of the World hit The New York Times bestseller list. Tor followed it up months later with another fat paperback, The Great Hunt. The series was quickly growing: a third installment, The Dragon Reborn followed a year later in November 1991, and a fourth, The Shadow Rising, hit bookstores in 1992. "We did a book each year, and each book built," Doherty said. "By the time we got to the fourth book, we were selling the first book in mass market paperback. It was hooking people and bringing them in. Then the next book would grow, because people wouldn’t want to wait."

By 1996, The New York Times profiled Jordan's rise, saying that he "may be an heir of sorts to Tolkien, in attention earned if not achievement," and that he had "come to dominate the world Tolkien began to reveal."

A Game of Thrones

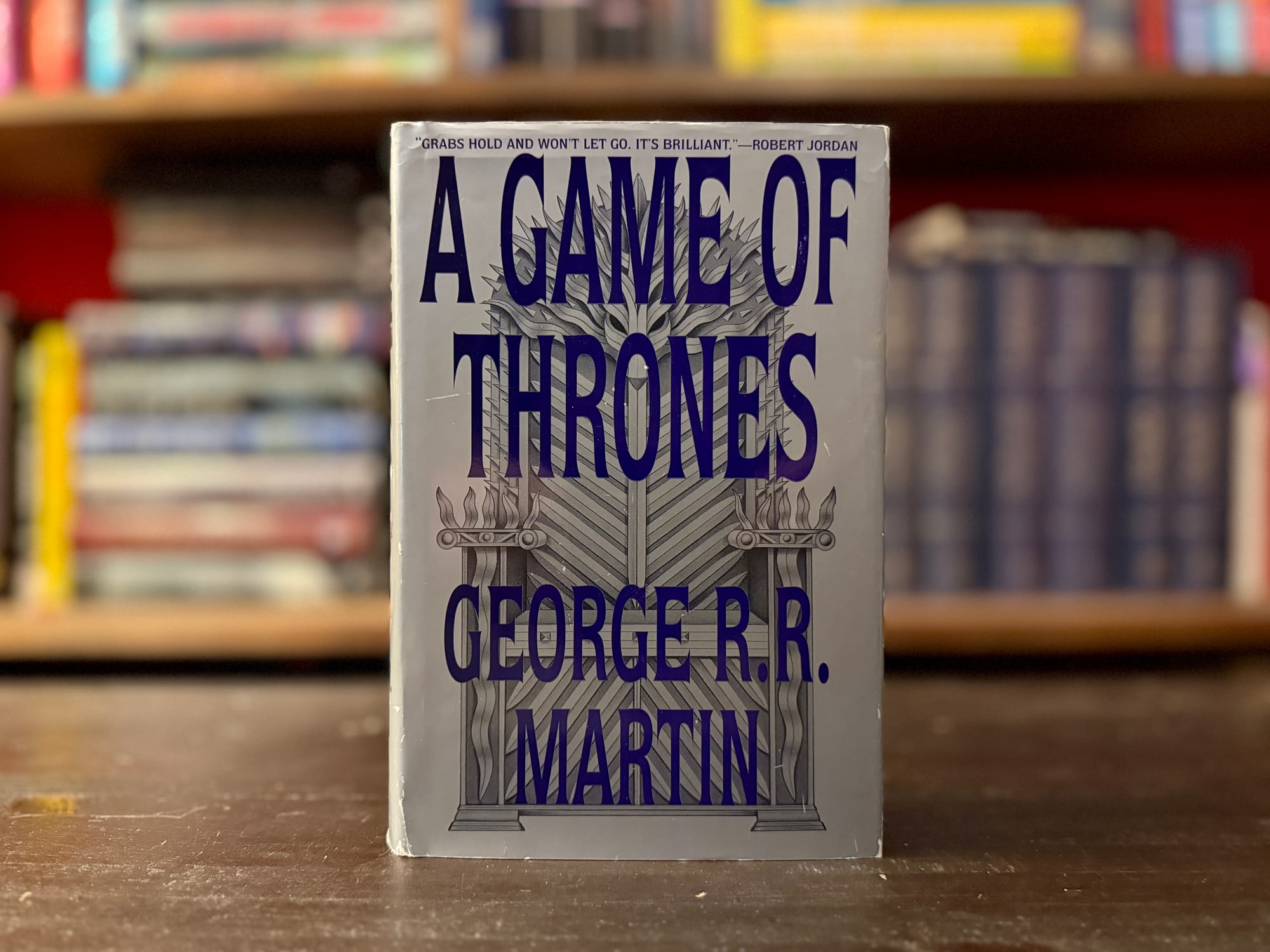

That same year, Martin was ready to jump into the fray. He and his agent sold the story as a trilogy to Bantam Spectra, and his publisher recalled that while they were enthusiastic for the first novel, they were cautious with their initial projections. "We costed our offer on modest sales in our territories – expecting, or should I say, hoping for, something like 5,000 hardbacks and 50,000 paperbacks," Jane Johnson, HarperCollins' publisher noted in The Guardian in 2016.

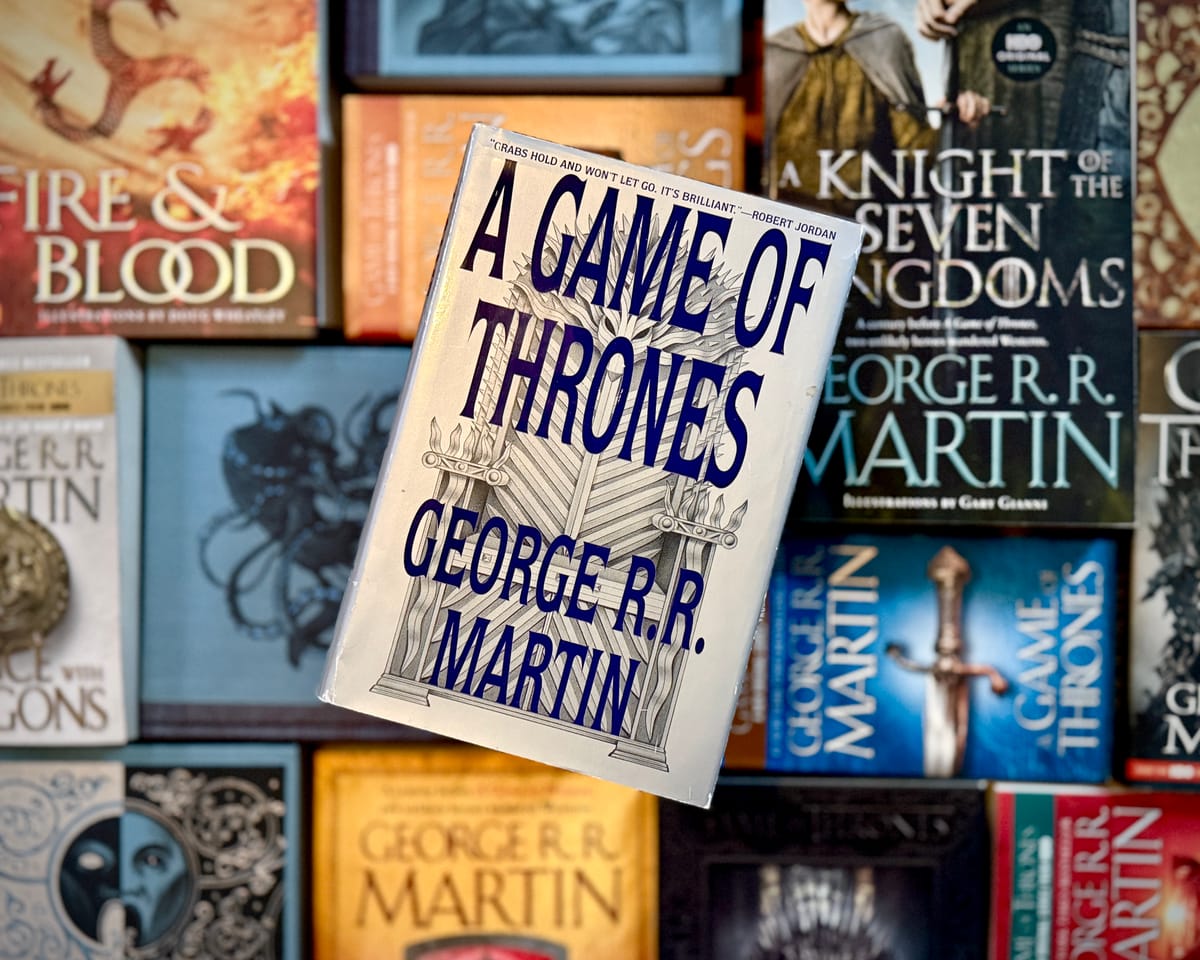

Publishers Weekly reported that there was an air of excitement around this new book: a bold return after years of exile, bolstered by an initial print run of 75,000 copies, along with a rave, starred review: "Although conventional in form, the book stands out from similar work by Eddings, Brooks and others by virtue of its superbly developed characters, accomplished prose and sheer bloody-mindedness...Martin's trophy case is already stuffed with major prizes, including Hugos, Nebulas, Locus Awards and a Bram Stoker. He's probably going to have to add another shelf, at least." The novel came with another important blurb" "Grabs hold and won't let go. It's brilliant," wrote Robert Jordan.

In July, Martin published a novella-length extract from the novel, titled "Blood of the Dragon," in Asimovs Science Fiction, and on August 1st, the book officially hit bookstore shelves. Two decades later, Martin described the release as "nothing spectacular." Reviews were excellent, but sales were just okay, with modest crowds at his various tour stops around the country. Johnson noted that "Initial sales were only moderately encouraging," but that they soon took off as "word-of-mouth recommendation was soon spreading like wildfire around fans. And it wasn’t long before we exceeded all of our original expectations."

A Game of Thrones introduced readers to the world of Westeros, a pseudo-medieval realm ruled by seven kingdoms with considerable political intrigue. Westeros has been at relative peace for years following the chaotic rule of Aerys II Targaryen, known as the Mad King. After his assassination, the surviving members of his family were exiled across the oceans, and Robert Baratheon, the leader of the revolution that toppled him took his place.

As the book opens, Baratheon asks a close ally, Eddard Stark, to become his hand, setting into motion a series of decision and actions that threaten the stability of the realm – there are plenty of questions about succession and bloodlines, loyalties and hostages, all coming together into a delicate series of alliances that hold feuds and grievances in check, but there are plenty of opportunists who're jostling for power and working their way up the chain of command.

Meanwhile, there are other threats: Viserys and Daenerys Targaryen, the offspring of the last king who went insane have been exiled, and work to plot their return to Westeros by recruiting the tribal members of the Dothraki people, and to the far north, a massive ice wall protects the realm from the northern tribes – and there are signs of the undead, which could threaten everyone.

The books resonated with readers, and while he and his publishers might not have characterized it as the wild success that Jordan enjoyed with his series, word was spreading. Fans quickly assembled fan website called Dragonstone, and in the next awards season, they were showing their appreciation: It earned the Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel from the readers of Locus Magazine and a Best Novel nomination in the 1997 World Fantasy Awards. "Blood of the Dragon" picked up its own set of awards: a Hugo Award for Best Novella, a second place finish for the same category in the Locus Awards, while Asimovs' readers awarded it third place in that year's readers choice awards. It also picked up nominations for that year's World Fantasy and Nebula Awards.

The book is a masterclass in writing: Martin lays out a vivid characters and their complicated relationships with one another, all in an engrossing world with a rich imagined history and lore that stretches back millennia. In Fantasy: A Short History, Roberts characterizes Martin's writing as the "pre-eminent work of Grimdark fantasy," and that his emphasis on a realistic vision for a fantastical realm helps to subvert expectations that helped it stand apart from the legions of Tolkien imitators that laid down ink before him. "Martin is interested not just in how an army fights on the battlefield," Roberts writes, "but in how it is mustered, where the money is coming from to pay for it, how its discipline is maintained," and that "this text's whole point is to deconstruct notions of honour, nobility, loyalty, and innocence, to reveal them for the whited sepulchers they are, or at least that the consensus nowadays believes them to be."

In 2005, critic (and later author of his own fantasy series,) Lev Grossman declared that Martin was the "American Tolkien," in no small part for this outlook: "What really distinguishes Martin, and what marks him as a major force for evolution in fantasy, is his refusal to embrace a vision of the world as a Manichaean struggle between Good and Evil...Martin’s wars are multifaceted and ambiguous, as are the men and women who wage them and the gods who watch them and chortle, and somehow that makes them mean more. "

"The tale grew in the telling"

With his epic saga off to a promising start, Martin now had to untangle some of the complications that he was making for himself.

During the release of A Game of Thrones, Martin told Publishers Weekly that he "recently come to the realization that I’m not going to be able to do it in three books, even though the books are bigger than I thought they’d be. I expected about 700 pages in manuscript, but the first one was close to 1100.” He decided to split the narrative into two novels, titling the next installment A Clash of Kings, and noted that his story would be a four book series, rather than a trilogy.

Like the first installment, his next was no less ambitious, with the story picking up after the ascent of Baratheon's young, sociopathic son Joffey to the Iron Throne and subsequent, shocking death of Ned Stark and depicts Westeros's descent into a civil war when Ned's son Robb declares himself "King of the North" and as others throughout the realm make their own moves for control of Westeros, all while the problems to the north and across the oceans continue to foment.

Some of that length came as a result of his experiences in Hollywood, he explained. "In Hollywood, [television] screenplays are very tight...Such economy can be a virtue, but at the same time there’s a richness in being able to create a whole world, in having the time to look at minor characters and allow things to happen on [the] side.” A Clash of Kings lived up to that, bringing in a handful of new viewpoint characters that added to the action and drama.

As he continued to write, he quickly realized that his four-book plan was quickly becoming unrealistic. Speaking with Amazon.com's Craig E. Engler in 1999, Martin explained that as the story was growing in that second, overflow book, he needed to take a hard look at the longer plan. "I actually called a halt for a while and I did some reorganization and I figured out how I could tell the story I wanted to tell and do justice to it, but at the same time not spend the rest of my life doing it. And six books seemed to be the most viable way to go." Three books became four, and then six.

Detours

The size and depth of Martin's world meant that there were plenty of other things to explore as well. He told Anders that " I do get distracted by other stories," and that he'd put his work on the books aside to explore those side stories and characters that bubbled up in his imagination. Two such characters were Dunk and Egg, a roaming hedge knight and his squire, who lived about a century before the events of A Game of Thrones, which he explored in a novella called "The Hedge Knight."

In a 2026 podcast interview, Martin explained that he had been approached by editor Robert Silverberg, who had just sold a major anthology, Legends: Stories by the Masters of Modern Fantasy. It was designed to showcase a series of new stories from major fantasy authors, including Terry Goodkind, Robert Jordan, Stephen King, Ursula K. Le Guin, Anne McAffrey, Terry Pratchett, and a number of others. "I signed a contract to write an original Westeros story," he explained. "It had to be a Westeros story, and then afterwards, I said 'oh god, what do I do?' I don't have a Westeros story for him, and I can't because [I've not finished the story yet!"

Martin realized that if he had to provide a story, it would have to be set before the events of his main story, and "then the idea came to me for what would become 'The Hedge Knight', beginning with Dunk. I wanted to tell a story that focused to some extent on the small folk, as I call them, on the people who were not lords."

He almost didn't make it, noting that Silverberg set a hard deadline: he would turn in his manuscript on January 1st. Martin turned it in on December 31st. When it was released in August 1998, the novella provided Martin's readers with a new sense of history and lore that further supported the larger world he was creating.

The story is small in scale, following Ser Duncan the Tall as he encounters Egg on his way to a tournament, where he hopes to prove himself and make a name for himself. Martin laces the story with names familiar to anyone who'd read the novels, lending a sense that the relationships and bonds seen in those novels have deep roots in this realm.

"That was one of the best decisions I've made as a writer," Martin explained. "Because in subsequent years, going to cons, I ran into a lot of people who would say to me, 'you know, I'd never heard of you before. I know you've been around a long time, but I'd never read any of your books. But I picked up Legends for the Anne McCaffrey story, but yours was the best story in the book." Those readers went on to seek out his novels, and Martin noted that he saw a real uptick in readers by the time his next novel hit stores.

A Clash of Kings hit stores on November 16th, 1998, and it became clear that the soft start to the series was temporary: it landed on The New York Times bestseller list, and shortly thereafter, a pair of fans named Elio M. García and Linda Antonsson, launched a fan site, Westeros.org, which included a forum that allowed fans to connect with one another and talk about the world, its characters, and the stories Martin was producing.

After his tour, Martin embarked on the next installment, titled A Storm of Swords, which he envisioned as a closure to the first big arc of the story that had been growing and growing. He provided updates throughout 1999 to fans, but by early 2000, he noted that he was running behind, and later explained that the manuscript had ballooned to 1,500 pages by the time he turned it in in April. But astonishingly, he wrote the entire thing in a year, a major feat, considering how sprawling the story and characters had become. It was also revealing another problem: he was hitting the upper limits to what a publisher could practically print and bind, and in some instances, foreign publishers simply opted to split the book into multiple volumes.

Speaking to io9 in 2013, Martin explained that the books were getting longer and longer, in part because of the momentum that the stories were taking: "You write a chapter and then in your next chapter, it can't be six months later, because something's going to happen the next day. So you have to write what happens the next day, and then you have to write what happens the week after that. And the news gets to some other place. And pretty soon, you've written hundreds of pages and a week has passed, instead of the six months, or the year, that you wanted to pass."

A Storm of Swords arrived in stores in the fall of 2000. Like its predecessors, it was a hit, hitting bestseller lists and earning Martin another Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel, along with nominations for the Hugo and Nebula awards.

With book three under his belt, Martin told fans that he'd be taking a short vacation before spending the summer working on copy edits and other pre-release details before diving into the next installment of the series, A Dance with Dragons. In the aftermath of the quickly-written Storm, he appears to have been confident that this next novel would come quickly, telling a reader to look for the book "sometime in 2002."

Powerhouse

Following the release of A Storm of Swords, the series and Martin's popularity began to snowball. While A Game of Thrones might not have come roaring out of the gate in 1996, word was spreading throughout the fan community with each successive novel. Writing in The New Yorker in 2011, Laura Miller noted that "it won the passionate advocacy of certain independent booksellers, who recommended it to their customers, who, in turn, pressed copies on their friends."

Martin and his novels were already enjoying the presence of a dedicated fan website, but that fandom was now translating into real-world turnout. At the 2001 World Science Fiction Convention in Philadelphia, a group of fans assembled for a dinner at a nearby restaurant, with Martin in attendance, calling themselves the Brotherhood Without Banners – a reference to a group of outlaws from the stories. They gathered again for a room party the next night, and over the course of the evening, one fan asked Martin to knight him. “I can’t knight you," Martin told him, "you haven’t gone on a quest yet!” The soon-to-be-knighted was sent off on a queset to acquire a Philly cheesesteak, and the group was dubbed the Knights of the Cheesesteak, beginning an informal tradition.

The Brotherhood Without Banners has continued as a grassroots organization with gatherings at other successive WorldCons and other conventions. "We go to panels," Xray the Enforcer, the "baroness" of the group wrote on its Westeros.org forums, "We sit on panels. We volunteer to help run conventions, site-selection voting, and at the Hugos ceremony. We throw parties. We hang out in the bar. We hang out with each other. Some of us cosplay. Some of us are into combat demos. Some of us just really dig books." As Martin went to conventions, book signings, and other events around the world, the Brotherhood often in attendance, a loose order of dedicated readers who were engrossed in his world, filling out seats and adding to the enthusiasm.

This level of fervent fandom is usually reserved for huge franchises like Star Wars or Star Trek, or established classics like Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. Martin had created a world and narrative that invited people to explore its rich details and relationships as he explored the trials and shifting balances of power between the characters and kingdoms, and it was turning casual readers into dedicated fans.

With the publication and promotional schedule for Sword complete, Martin turned to writing the next book in the series in early 2001 and immediately realized that he had a problem: the narrative would bring about some consequential events for the series: the arrival of Daenerys Targaryen from exile to Westeros, where she'd work to reclaim the throne. To bring up the ages of the characters and move past smaller events, Martin planned to advance the story by five years.

But once he began writing, he realized that a lot would happen in that gap; his characters would have undertaken plenty of actions that would need to be told through flashbacks – a lot of them. In a 2003 interview, he explained the problem he was facing:

"The structure of these books is extremely complex. I'm working with eight or nine different viewpoint characters, essentially writing a novel about each of them for each of these books and then weaving them together. What I found was that while the five-year gap worked admirably for some of those characters it didn't work at all for others. And I was skipping many events or relating them only in summary or flashback, many events which I feel could be very effectively dramatized, and would work better if dramatized.

After a year of struggling with the problem, he scrapped the time jump, telling attendees at a reading during the 2001 WorldCon that what would have been skipped over would now be a new book, A Feast for Crows. A Dance With Dragons would now become the fifth book in the series, and would be followed by the sixth and final installment, The Winds of Winter (While Martin stuck with the idea that this would be a six-book series, his then-partner Parris was already speculating at this point that he'd actually need a seventh book to contain it all.) By this point, it was clear that the hoped-for 2002 release date wouldn't happen.

With a new plan in place, Martin continued work on the novel, but work was coming along slowly. By 2003, he was reporting that the book was taking longer than expected, and that it was becoming difficult to contain the five years worth of story within it, and in an interview with Goran Zadravec in December, he explained that A Feast for Crows was proving to be the most difficult book in the series to write to date: "It still is a tough book to write. I'm still writing it, I'm still struggling with it."

One of the reasons for the difficulty was the number of characters that he was now juggling. Where A Game of Thrones started with only eight viewpoint characters, the character count for A Feast for Crows had more than doubled to 19 viewpoints, all of which had to be coordinated. Additionally, adding new characters required more story and context, he told attendees at Norescon 2004:

"At one point he was going to do a one chapter prolog that incorporated stuff from Dorne, and stuff from the Iron Isles. That became 2 chapters, then 12 (7 for one and 5 for the other). He realized he couldn't have a 250 page prolog that was all about characters that we have never met before, so he had to rip it up and start over. He wove the material in the prolog into the rest of the book."

In February 2004, Martin passed the 1000 page mark, and over the course of the year, reported that it was growing longer, something he hoped to avoid because of the problems that he and his publishers faced with Storm.

Along the way, he carved out time to return to another part of his world: Ser Dunk and Egg. Editor Robert Silverberg was assembling a sequel to his Legends anthology, Legends II: New Short Novels by the Masters of Modern Fantasy, which in addition to Martin, featured Terry Brooks, Raymond E. Feist, Diane Gabaldon, Neil Gaiman, Robin Hobb, Tad Williams, and a number of others. Martin contributed a new adventure of the duo: "The Sworn Sword", which followed them as they come to the aid of the people of Standfast, who're contending with a drought and a dam that a local lady has constructed to supply water to the moat of her castle and fields.

Like its predecessor, Martin uses the story to expand his world and shed some light on the lives of the people living in its feudal system. He was also apparently thinking about other stories in the world, telling his partner Parris that he wanted to write a trilogy "about one of the Targaryen Kings."

At the end of May 2005, he provided an update. A Feast for Crows wasn't quite done, but he was facing a now-usual issue: it was too long. "By January, I had more than 1300 pages and still had storylines unfinished," he wrote. "About three weeks ago I hit 1527 pages of final draft, surpassing A STORM OF SWORDS... but I also had another hundred or so pages of roughs and incomplete chapters, as well as other chapters sketched out but entirely unwritten."

He and his publishers began discussing what to do about it. He wasn't willing to make significant cuts to the stories, and didn't want to break the book into two parts. "It was my feeling that we were better off telling all the story for half the characters, rather than half the story for all the characters." They came up with a novel solution: split the dramatis personae in two. The two books would take place at the same time, but would each feature half of the characters. He had already wrapped up the storylines for the characters in A Feast for Crows (all relatively confined to one part of the world) and transferred the chapters he couldn't use to A Dance With Dragons (all clustered in another part of the world).

When A Feast for Crows was published October 17th, 2005, Martin closed out the book with an afterword that explained his decision to split the story up by characters. " Tyrion, Jon, Dany, Stannis and Melisandre, Davos Seaworth, and all the rest of the characters you love of love to hate will be along next year (I devoutly hope) in A Dance with Dragons."

It was a fateful declaration.

King Kong

A Dance With Dragons wasn't going as planned.

In December of 2006, Martin closed out the year on a dour note: "None of the projects I wrapped up was A DANCE WITH DRAGONS. Work has been going well, yes, but not especially on DANCE. I am not going to be able to finish it by the end of the year as I had hoped."

He was overly optimistic about his progress. When Martin announced the split between A Feast of Crows and A Dance With Dragons in May 2005, he closed on an optimistic note that the next book was already halfway done. "Looking at all the Tyrion and Daenerys material that I'd removed," he later explained on his blog, "I figured I only had another 400 odd pages to go to have another book of equal length, which was likely what prompted me to say the next book would be along in a year. Famous last words, those. Never again."

He later reported that much of 2005 was taken up with promotional duties for Feast, and that he came into 2006 with little progress. When he next sent in a partial draft to his publisher in 2007, the manuscript had shrunk. Martin provided a stream of updates on his blog, and noted that he was facing increased distractions and other obligations that were pulling him away from the book, including an extensive home renovation that took place over much of 2006.

In 2005, he noted that with the popularity of his novels came new opportunities, like audiobooks, collectables, comics, games, and interest from Hollywood, which carried with them a considerable amount of hidden work. "He thought it would just be giving an ok," a fan recounted after a convention, "and then he is involved in picking artists, approving text. All things he enjoys but which also reduce his writing time."

In 2006, Martin announced a companion guide to his series, The World of Ice & Fire: The Untold History of Westeros and the Game of Thrones, which he described as an illustrated, coffee-table book that would explore the history and lore of Westeros. He wouldn't be embarking on this project on his own, he explained: he enlisted the help of westeros.org founders Elio M. Garcia, Jr. and Linda Antonsson, who he frequently consulted about his world's details, who would help assemble the tome, which was eventually released in 2014.

He had other writing projects beyond his series as well. In 2007, he announced that he was partnering with friend and editor Gardner Dozois to helm a new anthology: Warriors, in which he would provide a new novella following the exploits of Dunk and Egg, "The Mystery Knight." It hit stores in 2010. The pair collaborated another other anthology after that, Songs of the Dying Earth: Short Stories in Honor of Jack Vance, which came out in 2011. On top of those projects, he was still helming his long-running shared-universe anthology series, Wild Cards, which saw five new anthologies hit shelves between 2006 and 2011.

There was another thing that arrived on his schedule that was beginning to take some of his attention away from the novel: a television series. HBO began adapting the series for television, and in the late summer and fall of 2009, Martin traveled overseas to watch his world come to life.

None of that was conducive of tackling the work he was undertaking. After rewriting and restructuring in 2006 and 2007, Martin noted that he began to move forward in 2008 and 2009, before really hitting his stride in 2010 and early 2011. In March 2008, he provided a brief update: alongside some new cover art for the book, he reported that "if I can deliver the book before the end of June, you’ll see these in your favorite bookstore sometime this fall. If I can’t, well… you’ll still see them eventually, I hope." Adding flames to the fire was his publisher, who listed a product page for the book with a September 30th release date.

I would be a year before he posted another update on his progress: "No, it’s not done."

"I made a lot of progress on the book in the first half of 2008. So much so that I was optimistic that I would be done by the end of the year. Unfortunately, I did not make much progress on the book in the second half of 2008. Indeed, I made some regress. Some of the reasons were literary, arising from problems in the narrative itself.

He was still optimistic, however: "I am trying to finish the book by June. I think I can do that. If I do, A DANCE WITH DRAGONS will likely be published in September or October."

Structurally, he had embarked on a complicated book: while he moved several hundred pages from Feast to Dance, he found that lining up those characters and getting them into the places where they needed to end up was tricky, and he wasn't able to complete the book by that summer or even the end of the year. In a February 2010 update, he outlined some of the difficulties:

"With all these characters scattered over my entire world, some chapters that span hours and others many months, various journeys and voyages to account for, not to mention the demands of the dramatic chronology, an entirely different matter than the literal chronology… well, it may well make your head explode. It did mine."

One of the biggest continuity and plot issues that Martin faced was what he referred to as the "Meereenese Knot," around a plotline involving Daenerys and several other characters. He characterized it as a series of actions that had to work around one another. "All of these things were balls I had thrown up into the air, and they're all linked and chronologically entwined," he explained. "And I had to write all three versions to be able to compare and see how these different arrival points affected the stories of the other characters."

This was a plot point that Martin struggled to complete, and he documented his attempts throughout the fall of 2009 before ultimately figuring out a solution months later in 2010: "At least part of the infamous Meereenese knot was a viewpoint problem. (Not all of it, no, a lot had to do with chronology and causation, but some of it was a POV question). Introducing a new POV [Ser Barristan Selmy] helped me resolve those problems."

It was during this time that the fandom that rose around his novels was proving to be a double-edged sword: Martin was increasingly facing criticism for the delay from throughout the fan community, especially as he blew past hoped-for release date after hoped-for release date. The delay provided plenty of fodder for readers to talk about it on social media, in message forums, blog posts, and on genre-related sites, commenting on its progress, pouring over every update he made, and sometimes getting into online shouting matches.

Martin was soon finding people complaining on his blog when he posted about going about his daily life when he wrote about his hobbies, love of football, travel, and other projects he was working on. In 2008, he issued a warning on his blog: "When I do open a post for comments, it’s because I want comments on the subject that I just posted about...I am perfectly aware that A DANCE WITH DRAGONS is late. There’s no need to remind me, thanks, I have plenty of editors and agents and publishers to do that."

It was clear that his frustration was mounting with his increasingly-vocal fanbase. In his 2009 update, he noted that readers were messaging him accusing him of making excuses for his slow progress, or outright lying about it, and he noted that he was becoming more and more reluctant to throw out a date when he thought he would be finished. Where he was once transparent about his progress, noting various chapters and characters he was working on, he was now more close-lipped, reluctant to mention dates or other details, lest they kick off a flurry of speculation. The fervor around Martin's progressed reached a point where even other authors were weighing in, with Neil Gaiman famously writing "George R.R. Martin is not your bitch."

Despite those challenges, he was making some progress: by the fall of 2009, he passed the 1,100 page mark, and by May 2010, the manuscript reached 1,311 pages. At New York Comic-Con in October, Bantam Spectra senior editor Anne Groell reported that Martin reported just five chapters left to go. On March 3rd, 2011, Martin announced that A Dance With Dragons finally had a release date: July 12th, 2011. The book wasn't quite done, he noted, but this wasn't like the prior hoped-for release dates: "this date is real," and in May, he confirmed that the book was finally complete: "Kong is dead."

The news spread throughout the internet like wildfire: the release date for the long-awaited book, Martin explained, was firm, and the only work he was doing on it was the behind-the-scenes copy-editing that supported the publication.

The timing worked out perfectly: HBO would soon debut its adaptation in April, providing Martin with a massive new potential audience for the series, which would cover the events of the first novel over its first ten-episode season. Anyone hooked on the series would have four, then five books to dive into to find out what would happen next.

By early July, all four books in the series hit The New York Times bestseller list, and the publicity efforts for the next was kicking into high gear: websites like Vulture put together chapter-by-chapter read alongs, Martin would embark on a massive, nation-wide tour, with booksellers and his publisher anticipating enough attention to impose restrictions for each of his events: many would require attendees to get a wristband or purchase a ticket, and then wait in line. To get as many people through signing lines as possible, attendees wouldn't be able to pose for photographs, get their copies personalized, or get any copies not purchased at the store (usually limited to 2-4) signed.

The book began hitting stores in July and was greeted with a wave of positive reviews. Pat's Fantasy Hot List declared that "delivers on basically all fronts. It's everything fans wanted it to be and then some! " Dana Jennings of The New York Times said that it "met the high standards set by its four siblings" and that Martin was "a literary dervish, enthralled by complicated characters and vivid language, and bursting with the wild vision of the very best tale tellers." Charlie Jane Anders of io9 proclaimed that the novel was "a brilliant, horrifying, depressing book that takes the characters Martin made you fall in love with, and plunges them just a little bit deeper into hell." Lev Grossman, who named Martin the "American Tolkien" just a couple of years earlier, said that "his skill as a crafter of narrative exceeds that of almost any literary novelist writing today," and that it was the best installment of the series to date.

The novel quickly hit the top of The New York Times' bestseller list, where it remained for weeks. When he finally had a chance to catch his breath four days later in Indianapolis, Martin reported that his events were drawing more than a thousand people at each stop, and that "DANCE had the highest first day sales totals of any work of fiction released this year. Not just SF and fantasy, but all categories of fiction."

It was a tremendous, overdue moment for Martin. He – and his readers – now turned their eyes towards the next moment in the saga, The Winds of Winter. Everyone hoped that it wouldn't take another six years to arrive.

Back to Hollywood

In 2008, HBO debuted a new television show: True Blood, an adaptation of Charlaine Harris’s Southern Vampire Mysteries series. The story was set in a world where supernatural creatures existed and in which vampires began to come out to the public after the invention of a synthetic blood. The series earned widespread acclaim for the network. “The success of True Blood proved to [HBO CEO Richard] Plepler and his colleagues that HBO could make waves in the fantasy genre — an important realization for the network,” wrote Felix Gillette and John Koblin in their book Its Not TV: The Spectacular Rise, Revolution and Future of HBO, and quote creator Alan Ball: “it opened the door for them to do other genre and sci-fi stuff they might otherwise not have done.”

Science fiction and fantasy projects were widely growing in popularity in the early 2000s. George Lucas had released his Star Wars prequel trilogy, while J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter novels and subsequent adaptations were drawing enormous followings in bookstores and movie theaters. But it was in December 2001 that Hollywood discovered that audiences were clamoring for fantasy: Peter Jackson released The Fellowship of the Ring, the first adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. The subsequent films, The Two Towers and The Return of the King hit theaters in 2002 and 2003, earning considerable acclaim and success at the box office. For a series long considered unadaptable because of its length and detail, Jackson showed that such projects were not only doable, but could be done well.

As the success of A Song of Ice and Fire rose in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Hollywood began to take notice, and Martin began taking meetings to talk about potential projects. In most cases, he was nonplused: he had long been frustrated with the constraints that productions placed on his imagination, and his fantasy series was his way of making sure that everything he wanted to put into a story was in there.

Over the years, he described pitches where screenwriters wanted to focus on only specific characters, or change significant plot points to fit the stories into a film, and often mused that the only way to do it properly was to go big: a television series – some fans suggested that HBO, as a cable network known for not shying away from blood and sex, would be an ideal home for such a project. In 2006, screenwriter David Benioff and his writing partner D.B. Weiss read the books and began thinking about adapting the story as a television series. They soon arranged to meet with Martin, and over the course of five hours, impressed him with their knowledge and appreciation of the series.

He gave them his blessing, and the pair began working on their pitch to networks, eventually landing at HBO, which announced that it had optioned the books for a series. Benioff and Weiss "impressed the hell out of me, and I’m really looking forward to working with them," he reported on his website. "They’re both bright, passionate, enthusiastic. They know the books inside and out, they get the books, and they’re committed to bringing my story to your television screens… not a vaguely similar story with the same title (ala Earthsea, or what passed for same on the Sci-Fi Channel). A Song of Ice and Fire should be in very good hands."

Work continued in the background for more than a year, and in November 2008 the network ordered production for a pilot episode for the series, titled Game of Thrones. Benioff and Weiss, along with director Tom McCarthy shot the episode on location in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Morocco in October 2009 and wrapped in just under a month.

From there, they cut the episode and began screening it for friends and family, and then for HBO, where they got a rude awakening: it was bad.

"You guys have a massive problem," Craig Mazin (who later went on to create Chernobyl and The Last of Us for HBO) told them, and network executives concurred. As relayed by James Hibbard in Fire Cannot Kill A Dragon: Game of Thrones and the Official Untold Story of the Series, executives felt it looked small, that the tone felt off, and they had concerns about the balance of realism and fantasy. "I liked the pilot," Martin said, but "I realized later that I was a poor person to judge because I was too close to it." Benioff and Weiss knew their series had a number of problems and went to HBO with a plan to fix it. Executives later recounted that they knew there was something good there, but they needed to really work to bring it out. They did something almost unheard of for a potential project: they gave it a second chance by ordering it to a series in March 2010. The pilot would be reshot and some of the actors would end up being recast.

A year later, Martin announced the release date for A Dance With Dragons, and HBO planned for a release in April. Benioff and Weiss solved the problems that plagued their initial pilot episode, and the series landed with a wave of acclaim from reviewers and fans, who praised its sense of realism and serious take on the genre. More than 2.2 million people tuned into the network to watch the first episode, and ratings grew over the course of the first season – much like Martin's novels, word of mouth proved to be a critical factor.

Two days after the premiere, HBO announced that the series would get a second season, and when it returned, even more people watched. Over the next six seasons, viewer numbers grew, eventually reaching tens of millions of people around the world over the course of its eight-season run.

Game of Thrones was a massive hit, thanks to a handful of factors. Its source material was already wildly popular, not just within hardcore genre fans, but within a wider, genre-friendly audience. Science fiction and fantasy projects were growing in popularity, thanks to shows like the SCIFI Channel's Battlestar Galactica reboot and ABC's LOST, which were also changing viewer preferences from shows with an episodic structure to ones that were driven more by the narrative.

And on top of all that, the story that Martin created was big and complicated, with tons of characters and their relationships, all depicted in a way that felt modern. Remove its pseudo-medieval and fantasy trappings, and you had characters interacting in ways that felt recognizable, with goals and motives that anyone could relate to.

There were other, bigger things in the cultural zeitgeist at the time that helped prime Game of Thrones for the wild success that it enjoyed over the course of its run. Science fiction had been popular at the end of the 20th century, fantasy was rising in popularity and taking its place. "It was an incredibly interesting moment," Lev Grossman (The Magicians) told me in an email when I asked him why the books and story resonated at this point. "We think of science fiction as the genre that critiques and processes technological change, and obviously it does, but fantasy does a lot of that cultural work too. The first big boom in 20th century fantasy followed a time of huge traumatic technological change: WWI, mechanized warfare, the rise of the car, movies, TV and so on. I think that in the 1990s we needed fantasy to respond to the rise of the Internet and the increasing penetration of technology into our personal lives."

Another author, Brian Staveley (The Emperor's Blades), pointed out another reason: Harry Potter had been wildly successful in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and as those readers grew up, there was a lot of interest in more mature and sophisticated stories. "Harry Potter made it acceptable for anyone--not just the weird kids--to read fantasy," he noted. "and when those readers grew up, a lot of them found Martin. The explosion of Game of Thrones onto HBO just solidified fantasy's place in the pop-culture mainstream."

The series also arrived at a time when television was changing drastically. In 2013, Netflix debuted a new series, House of Cards, a political drama that telegraphed its intentions. No longer content to just rent and mail films and television shows to subscribers, the streaming service was wading into the world of original content. Netflix executives said “ The goal was to become HBO faster than HBO could become us.”

HBO was paying attention: In 2010, it launched such a platform, HBO Go, available to the network's subscribers, first for computers and the network's website and the year later, as a mobile app for iOS and Android users. With shows like Game of Thrones doing exceptionally well, HBO began looking for other projects that would appeal to that audience, eventually releasing a genre-bending mystery series True Detective in 2014. Demand for these shows overwhelmed HBO Go, often crashing due to the demand. Later that year, HBO announced that it would release its own standalone streaming service, HBO Now, which would provide a means for non-HBO cable subscribers to consume the network's programming.

By this point, Game of Thrones was the biggest television show in the world, earning armfuls of awards for its cast and writers, and driving HBO and its nascent streaming service to new heights. And by 2015, the series had begun to run into a new problem: they reached the events of A Feast for Crows and A Dance with Dragons and were beginning to run out of material to adapt.

Martin had long hoped that he would be able to stay ahead of the showrunners by publishing A Winds of Winter prior to the release of Season 5. "I thought Feast for Crows and Dance with Dragons would be recombined, because you can't separate them the way I did in the books, and I thought there would be three seasons there, he explained, noting that the show abbreviated some of the events that took place in books four and five. "I thought I had three years to get out the next book, and suddenly I was racing to get it out before season five."

In an interview with Variety ahead of the season premiere, Benioff noted that things would begin to diverge from the books a bit starting in the sixth season. "We’ve had a lot of conversations with George, and he makes a lot of stuff up as he’s writing it. Even while we talk to him about the ending, it doesn’t mean that that ending that he has currently conceived is going to be the ending when he eventually writes it."

But it was becoming clear that the series would pass him, and in 2013, Benioff and Weiss met with Martin to learn where he was headed. "It wasn't easy for me," Martin later recounted in Fire Cannot Kill a Dragon. "I didn't want to five away my books. t's not easy to talk about the end of my books... I told them who would be on the Iron Thrown, and I told them some big twists." Martin was able to provide them with a general roadmap of where he was thinking, but not the specifics. The story would now diverge, with the series running on its own momentum, and Martin plugging away on his overdue tome.

Game of Thrones ended with a six-episode eighth season. Its sixth season worked with as much material from the fourth and fifth novels as it could, but was also incorporating elements that Martin released from The Winds of Winter, while the next two seasons plunged into entirely new territory guided by what Martin had revealed to them. The results were mixed: the show was more popular than ever, but it was also clear that the show benefited tremendously from Martin's work, with many critics criticizing the way the final season wrapped everything up.

On his blog, Martin praised the show, but noted that his ending to the series wasn't the same as what Benioff and Weiss created. "I am working in a very different medium than David and Dan, never forget. They had six hours for this final season. I expect these last two books of mine will fill 3000 manuscript pages between them before I’m done… and if more pages and chapters and scenes are needed, I’ll add them."

Blowin' in the wind

As soon as he announced the release of A Dance With Dragons in March 2011, Martin acknowledged that there was more story to tell. "Enjoy the read. Me, I've got another book to write. Yes, climb right on my back... and what a cute little monkey you are..."

Like A Dance With Dragons, Martin took some of the material that he'd written for the prior book, and shifted it to the next, giving him a bit of a boost going into The Winds of Winter. He posted a handful of early chapters to his website, but had largely abandoned the regular progress updates that he had been posting to his blog.

That was probably to stave off questions about his activities and commitment to the project, something that continued to plague him, even as other projects and opportunities arose. Following the release of the fifth novel, Martin embarked on a massive publicity tour and was heavily involved in the television series, ultimately writing four episodes in the first four seasons.

There were a number of writing work that took up his attention as well: In 2014, he released a long-in-the-works companion book, The World of Ice and Fire: The Untold History of Westeros and The Game of Thrones, co-written by Eliot M. García Jr. and Linda Antonsson. The year before, he published a new anthology co-edited with Gardner Dozois, Dangerous Women, which contained a novella titled "The Princess and the Queen," about the fight for the Iron Throne between Crown Princess Rhaenyra Targaryen and Queen Alicent Hightower, long before the events of the main series, and which were originally been intended to be included in The World of Ice & Fire, only to be cut for length.

Other stories from cut from that tie-in book found their way into print in other anthologies. In 2014, he and Dozois edited another volume, Rogues, in which he provided "The Rogue Prince, or, a King's Brother", about King Viserys I Targaryen, and in 2017, Dozois released Book of Swords, which included the novella, "The Sons of the Dragon," about Aegon the Conqueror. He was also busy repurposing other existing stories: in 2015, he brought the three "Hedge Knight" novellas together into a single volume, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms.

"These histories began a few years back as a series of sidebars intended for THE WORLD OF ICE & FIRE, our huge illustrated concordance," he explained, "but I got carried away (as I tend to do) and before long the sidebars got so long they were threatening to overwhelm the entire book, so we pulled them out of that volume… and saved them for this one."

That material would now form the basis for a new book: Fire & Blood, which he cautioned wasn't a novel, but something a little different. It was also, he wrote, the first of two volumes, and which he hoped would be out before Winds: "regulars here may recall our plan to assemble an entire book of my fake histories of the Targaryen kings, a volume we called (in jest) the GRRMarillion or (more seriously) FIRE AND BLOOD. We have so much material that it's been decided to publish the book in two volumes." The novellas he published in the anthologies were just abridged versions, he said, and this would expand the world. A second volume, he noted, "will carry the history from Aegon III up to Robert's Rebellion, is largely unwritten, so that one will be a few more years in coming."

It seems that it was something of a needed distraction for Martin, who closed out by saying "Archmaester Gyldayn is hanging up his quill for a while," and that he was returning to work on The Winds of Winter, which he had continued to work on. Work on the book was progressing, and he told a fan that it had gotten to the point where his publisher suggested splitting it into two volumes, something he resisted.

He also remained heavily involved in the television franchise, signing a major, five year deal in 2021 with HBO to continue to develop projects in the post-Game of Thrones world, of which the first out of the gate was The House of the Dragon, an adaptation of Fire & Blood. While a number of others were in contention, although not all of those made it out of development.

Later, he noted that he wished that he had focused more on Winds of Winter. "I was red hot on the book and I put it aside for six months” he told James Hibbard in 2015 “I was so into it. I was pushing so hard that I was writing very well. I should have just gone on from there, because I was so into it and it was moving so fast then. But I didn’t because I had to switch gears into the editing phase and then the book tour. The iron does cool off, for me especially.”

"Get back to work, George," had already become something of a cultural meme. With the television adaptation barreling ahead, there was now even more attention on Martin's deliberative pace, summed up neatly in a performance at the 2014 Emmy Awards when Weird "Al" Yankovic performed a medley of the year's theme songs, closing out with "Type, George, type as fast as you can. We need more scripts... write them faster write them faster write them faster!" all while someone delivered a typewriter to a bemused Martin, who was sitting in the audience.

Nearly a decade and a half later, the book remains unfinished.

There have been signs of progress: In during the COVID-19 lockdowns, Martin explained that had written "hundreds and hundreds of pages" of the novel, and that 2020 was "The best year I’ve had on WOW since I began it. Why? I don’t know. Maybe the isolation. Or maybe I just got on a roll. Sometimes I do get on a roll."

Martin revealed in an appearance on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert in 2022 that it would likely surpass the length of both A Storm of Swords and A Dance With Dragons. "I think I'm about three quarters of the way done. I'm done with some of the characters."

A year later in 2023, he reported that he was still making progress "And, yes, yes, of course, I’ve been working on WINDS OF WINTER. Almost every day. Writing, rewriting, editing, writing some more. Making steady progress. Not as fast as I would like...certainly not as fast as YOU would like…but progress nonetheless," and in 2025, he reiterated his frustration with the complains that the book was overdue.

"Some of you will just be pissed off by this, as you are by everything I announce here that is not about Westeros or THE WINDS OF WINTER...And I care about Westeros and WINDS as well. The Starks and Lannisters and Targaryens, Tyrion and Asha, Dany and Daenerys, the dragons and the direwolves, I care about them all. More than you can ever imagine."

In 2026, Martin spoke with James Hibbard for a lengthy profile in The Hollywood Reporter, he explained some of his process:

“I will open the last chapter I was working on and I’ll say, ‘Oh fuck, this is not very good.’ And I’ll go in and I’ll rewrite it. Or I’ll decide, ‘This Tyrion chapter is not coming along, let me write a Jon Snow chapter.’ If I’m not interrupted though, what happens — at least in the past — is sooner or later, I do get into it.”

He reiterated that he was committed to finishing the book, but it was also clear that he was exhausted. There had been problems and conflicts during the production of The House of the Dragon between him and its showrunner, and faced a fan at the 2025 WorldCon who pointed asked him if he would hand the series off to another writer because "you’re not going to be around for much longer."

The book remains a priority, he said, and if he can free up his schedule and commitments. "I could finish The Winds of Winter pretty soon."

The future

What comes next? Certainly, work on The Winds of Winter, which has dragged on far longer than Martin and everyone else would have liked. Looking over the course of his career, a couple of things have become clear:

Martin has created an incredibly complex world, one that has ballooned in length in the telling. From the earlier stages of his career, it's been clear that he's committed to the meticulous details of his world and story, one that he's been immersed in for thirty years. That complexity brings out its greatest appeal: characters and relationships that have attracted the attention of fans for successive decades. It also provides a stumbling block: with so many characters and storylines, he's made a lot of work for himself, work that requires lots of coordination, editing, rewriting, and deliberation as he moves forward.

There's also a lot for him to do, not just for the book in front of him, but as the center of this much larger world. A new series based on A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms just debuted, which comes with a second season already greenlit, while a third season of The House of the Dragon is due out sometime later this year. A fourth and final season is in the works. Other spinoffs are also in the works, now an integral part of Warner Bros.' content library, alongside such juggernaut franchises like the DC universe and the Wizarding World, and The Lord of the Rings. He's also said that he plans another Fire & Blood, has story ideas for up to 12 Dunk and Egg novellas, and a handful of other related projects. And then of course, the pressure will be on for A Dream of Spring, the final installment of the series.

If there's anything that I've found in the research and writing of this piece, it's that Martin is a perfectionist who's been dedicated to producing a book that he's happy with. This is not a work of content, which is where I think the conflict between him and his fans originates. It's a situation that I suspect is frustrating to everyone involved, and hopefully, he'll be able to find a way to navigate it in the years to come.

Since its publication 30 years ago, A Game of Thrones and its sequels have probably become some of the most important works to the fantasy canon since Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. Martin's background in science fiction and his attention to realism and detail have prompted him to overcome the fantasy genre that arose in the aftermath of Tolkien by running counter to the tropes and trends that authors produced for an audience ready for more.

Grossman pointed out that this is because of the quality of Martin's work. "his work was so structurally sophisticated, and morally complex, and so grounded, in politics and economics and the psychodynamics of royal families, it had the texture of great narrative history."

Alongside authors such as Rowling and Pullman, Martin helped transform an entire genre and fandom into a powerful force in mainstream popular culture, supercharged by the adaptations that introduced him to so many new readers and fans, who turned phrases like "winter is coming" have become widespread, mainstream touchpoints.

"In general, the Game of Thrones franchise has been great for fantasy writers." Michael A. Stackpole explained to me in an email. "It's raised the genre in visibility so folks understand what it is we do. Any writer can use GOT (books or TV) as a jumping off point to explain things through comparison and contrast." Staveley concurred, pointing out that Martin helped plant the seeds for the next generation of writers. "Lots of people have written about how Martin (along with Abercrombie, Jemisin, et al) set out to upend pretty much all of the standard fantasy tropes," and that "the explosion of Game of Thrones onto HBO just solidified fantasy's place in the pop-culture mainstream. Now that the door is open, I think a lot of writers who are quite unlike Martin can actually get eyeballs on their books just because those shelves are bigger and more popular in the bookstores..."

Hopefully, Martin will be able to finish out his remarkable saga, finding an end for his characters and their respective fates. Along the way, he's had an astonishing career, one that has utterly transformed the face of fantasy literature and raising the bar for those who'll follow in his footsteps.

Thank you very, very much for reading. Much like Martin's writing, this started out as a shorter piece, designed to explain where A Knight of Seven Kingdoms came about, only to turn into this much larger piece.

I have a handful of people to thank for their assistance with this piece: Ellen Liptak, Eric Barber, Tom Hopper, Cara Gorman, Michael Gorman, Mike Anton, and Robert Barker for help with the extra copies and photographs that I used for this piece. I'd also like to share my appreciation for the folks at Westeros.org for their long-running and detailed curation of Martin's comments throughout the years. And thanks to Lev Grossman, Michael Stackpole, and Brian Staveley for their comments.

I really like researching and writing these types of lengthy, behind-the-scenes explorations of how stories come about. I learn a lot from researching them, and I often find that there are lots of interesting influences and developments that take place that shape how these stories come about.

If you enjoyed this one, you might enjoy some of the others that I've written:

- The Expanse

- Dragonlance

- Harlan Ellison's Dangerous Visions

- The Star Wars Expanded Universe

- Lev Grossman's The Magicians

- Syfy's Dark Matter

- Hugh Howey's Wool

- John Scalzi's Old Man's War

As I noted at the top, if you'd like to see more, the best way to do that is to sign up as a supporting member. You can also leave a tip or purchase a book via one of the affiliate links in the piece, and if you're new, sign up to get further installments of Transfer Orbit in your inbox. I've got a lot planned for 2026.

Changelog

- January 21st, 2026 edit: added section "Detours" after discovery of a new interview that added information about the Hedge Knight stories. Fixed typos.