Writing Slate

/So, I've been doing a bit of independent projects with history since I've graduated, both centered around the history of Camp Abnaki. I started this summer with archiving a lot of the records and sorting them out in house, and from there, I embarked on two projects:

1 - Comprehensive History of Camp Abnaki. This is going to be an extremely long-term writing project, given the scope of what I'm trying to do. Rather than just writing a history paper that essentially goes from point A to B to C to D, this project is going to look at the history of Abnaki in the context of 20th century history - how major events such as the stock market crash, the first and second world wars, the cold war, outbreak of flu, the 1960s and how attitudes towards child care have been changing since 1901. This is going to take me a long time to finish, and it's currently on the back burner due to it's size and due to the next project:

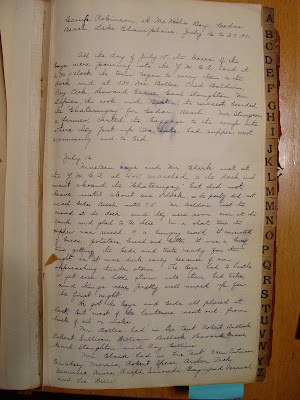

2 - The life of Byron Clark. This paper's in a more complete form now, standing at 25 pages, with probably another ten or so to be written. I've just gotten Clark's journal, which I'm working on translating from cursive to a regular text file. However, in order to finish this in time, I'm going to have to forgo some of the translating and pick out sections where needed. I currently have one feeler out for a presentation at a historical conference in April, and I'm hoping to get this published (it will probably need to be edited down.) I've also currently put out requests for editing from three PhDs that I know.

3- Norwich University and the Invasion of Normandy. This was my thesis paper for my senior year at Norwich, and while I completed it for the course, topping out at 38 pages (50 with maps and sources), I'm not at the point where this is finished for me. I need to visit the National Archives and pull unit records for various infantry and armored divisions, which I found to give incredibly detailed information on the going-ons of the campaign. This is something that I'd love to get published someday.

4 - The Class the Stars Fell On - this is going to be my next project, and I'm going to start it right after I finish with my Byron Clark Paper. I came across the reference earlier this weekend when I finished Rick Atkinson's An Army At Dawn (FINALLY), when he mentioned that the American Military Academy (West Point) class of 1915 numbered 162 graduates. Out of that class, 59 were made general, two of them reaching the highest rank possible, five stars (Eisenhower and Bradley). Following that, there were two 4-star generals, seventy-three 3-stars, twenty four 2-stars and twenty four 1-stars. The intent it to examine what role this class played in the world following their graduation and why this class was so extraordinary - no class since has graduated as many people who obtained the rank of General. This will probably be a long project as well - possibly book length. I know that there's a lot of information, particularly about the more visible members of the class, such as Eisenhower and Bradley, but I'm going to need to research a lot of other people, to see what they were up to. I'm excited for the prospect of this project, and I suspect that it'll take me a bit longer than I'd like because I'll be starting my Masters in March, although maybe this can be a part of it.