John Joseph Adams might have released his first anthology celebrating Lightspeed Magazine's first 12 months of outstanding stories, but Friday marked my own Year One with Lightspeed, and man, what a year it's been, working first as a slush reader, and now as one of the magazine's Editorial Assistants / Social Media person. I was a bit reluctant at first when asked, worried that I might be sucked into a world of terrible stories that I'd never get over. I found the contrary: slush reading has been an outstanding lesson in and of itself on what goes into an outstanding story, and there's a lot of good fiction that gets submitted. Over the last year, I've read hundreds of stories: some great, some bad. Over the last year, I've learned a couple of things from my work there:

First, a couple of disclaimers:

- This isn't a how-to guide on how to get a story directly published in Lightspeed Magazine, other than that “write really well” is sort of the catch-all for every publication out there.

- This is just my viewpoint, not Lightspeed's.

Rejections happen... a lot.

Lightspeed Magazine currently has 96 slots for fiction. Scratch that, half of those are reprints. You're left with 48 slots of original fiction. If you only write in one genre, cut that in half again: 24 slots for new, original science fiction stories and 24 slots for new, original fantasy stories. On the other end? There's a lot of authors submitting stories for those precious few slots every single day. That's a large pile of stories that comes to us, far more than we could ever hope to publish. The result is a ton of letters going out saying thanks, but not this time.

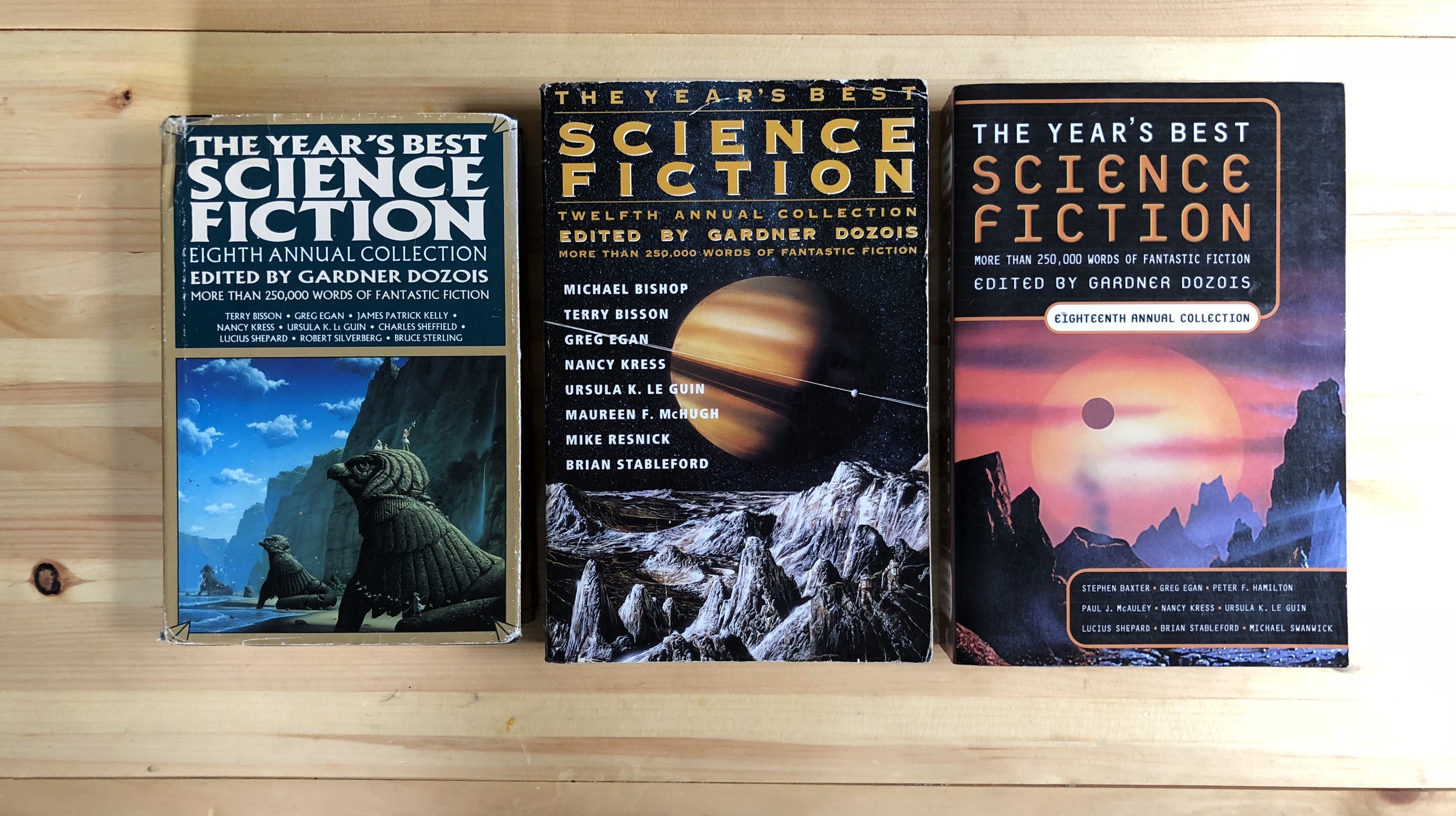

Getting past the slush readers requires one thing: a story that blows us away from the first page, and holds our attention. It has to hold the attention of others at the magazine: what works for one person might not work for someone else. Ultimately, the stories run the gauntlet, and are whittled down. The intended effect here is that we come out with a stable of short fiction that we're willing to stand behind. The result speaks for itself, I think: I've seen a ton of our stories on the “Best of” lists and end-of-the-year anthologies in the last couple of months. The magazine was nominated for a couple of Hugo Awards in its first year, and I've little doubt that we'll be listed in the next year. (I've got a couple of stories that I'd love to see win a shiny rocket, personally.)

Your Best Work Matters

Personally, I'm a stickler for detail, and the slush work has improved my own stories quite a bit, and my own submissions process:

1: refer to Christie Yant's blog post on cover letters and submitting, and follow it to a T. When I'm reading a story, it's useful to know if you've attended Clarion or you've been published in X, Y and Z magazines, but not things like “'I'm sure this will be rejected, but you never know'”: you don't need to give us reasons to reject your own story ahead of time.

The same diligence goes for grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, weird formatting and so forth. This is a fantastic guide to refer to when it comes to the format of a manuscript. The font doesn’t bother me (provided it’s readable), but it’s good to make sure that you’ve read it through more than once, and that it’s not overly difficult for someone to read. Spelling and grammar can be easily fixed, but broken stories are harder. Remember, you're asking the magazine (at least, if you're submitting to a magazine that pays money) to buy something from you, which they in turn ask people to buy in a bound package, printed or otherwise. If someone hasn't put in the effort to carefully read over their story and put it through the ringer, what else haven't they done their due diligence on? Characters? Dialogue? Worldbuilding? If my faith in the story is shattered early on, it's hard to regain that as I read on.

2: After submitting, wait for a response, and then repeat. And repeat again.

Structure, characters, ideas, story

In 2008-2009, I wrote a handful of stories, and half-heartedly submitted them to a couple of markets, where they were pretty promptly rejected. I did the same thing when I was in high school, and received a couple of rejections before getting dejected myself. I've since written stories in 2011 that I'm much, much happier with.

Slush reading has done a couple of things for me: it's shown me that there are stories that go out on their first submission and get bought pretty quickly. (It doesn't happen often, but when it does, those stories are pretty amazing.) There's other authors that dutifully submit numerous times, improving each time, before we find something that we like. There are also a lot of stories that get a read through and are rejected. There are lessons to be learned from both: a story that's published is a great example of what it takes to be published. A story that's rejected is a great example of where there's something wrong with the story.

Plausibility is a big thing for me. Fiction is a window into our everyday lives, with an idea behind it that helps us better understand the world around us. The individual actions of the characters, what they say to each other and their motivations all contribute to some central point that is revealed through what happens. Often times, I come across stories where something doesn't quite fit: the character's motivations aren't clear, the dialogue isn't there or something along those lines, but underneath all of that, there's something in the world that the author has created that doesn't line up for me. Sometimes, it's as simple as a plot device that, when under scrutiny, doesn't make sense: A cyberpunk story where technology is obviously advanced, but the thinking behind the story hasn't caught up with the technology. Thinking to myself “why is this happening” isn't generally something that should be happening while reading it.

In other instances, I find myself asking the following question: how is this contributing to the style of story that it belongs to: does a time travel story warning of the dangers of killing one's grandfather add anything new or different to that? If no, I have to find a way to justify recommending it. (That's not to say that we won't get a story like that, that's worth publishing.)

In my own writing, I've found that I spend a lot of time planning out what's going to happen, trying to figure out what the best intersection between the idea that I've had fits with a set of characters, the world and its own rules, and what the characters do to best display said idea. A lot of ideas end up in the trash, or filed away for later. I'm still working at it.

Keep at it & learn from your mistakes

I see authors submit multiple stories, and I see people who've submitted for the first time. What I love seeing is an author who submits a story, and soon, comes back after with another story that's better. I hope, that once we reject a story, an author will go ahead and take a look over it again: something happened that made it a poor fit for the market, and in between my own submissions, I go re-read stories and see if there's something that's tripping them up somewhere. Even once a story is accepted somewhere, it goes through an editorial process that will further change the story. From my own experience with various military history projects, there's always something to improve, depending on the day, the mindset that I'm in, and so forth.

My own efforts at fiction are long processes: I plan, write and set aside for a month or two. I go back, revise (or throw out) and repeat. The story goes to a couple of beta readers, and comes back with edits. I try and get stories that improve from story to story. Hopefully, I'll look back on what I've written now at some point and find that I've improved from that point on, either with greater experience, different mindset or writing ability.

The key point is to continue to submit, and to realize that rejections aren't some sort of personal vendetta, but reinforcement that nothing less than the best will cut it. With that in mind, I go back, edit and try again, until I can get to that point.

Even once a person has sold a story, there's no guarantee that I'll like their next story; it's happened before.

I've yet to attend a writing workshop (recently - I am a very happy alum of the Champlain Young Writer's Conference, held every year in Burlington, Vermont's Champlain College), or writer's group, but the best educational experience that I've had is by far working in the middle of a slush pile. It's provided me with tons of examples of what not to do, what to do better, and what absolutely every story needs to have: a reason to turn to the next page. I'm looking forward to what the next year will bring.

(And, if I haven't scared you away with all that, submissions have changed.)

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10310465/akrales_171212_2179_0245.jpg)