Customers Aren't Idiots

/

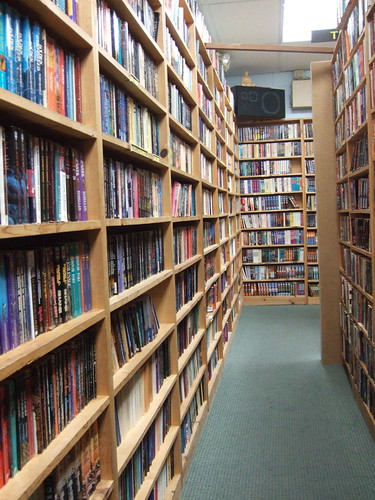

While driving home over the Thanksgiving weekend, Megan and I talked about our respective retail experiences. I had worked at Waldenbooks/Borders for several years, while she had worked at Borders, Fashion Bug and Weis, a grocery store in the Pennsylvania area. It's not a stretch to say that we're both fairly disillusioned with how things worked in each of the stores, but I don't believe that the retail experience has to be bad for either the customer, or the people working there. There are certainly plenty of examples of places that are fairly decent to work for, and there were points in both of our stores where we felt that we enjoyed what we did.

The crux of the problem seems to lie in a band between the upper management to direct the strategic concerns for whatever company you're working with, and the people on the ground level: the middle manager level seems to be the biggest issue, because it allows for the priorities, directions and strategy from the upper echelons to be interpreted, translated and carried out, and in each of our cases, this was where things went very wrong.

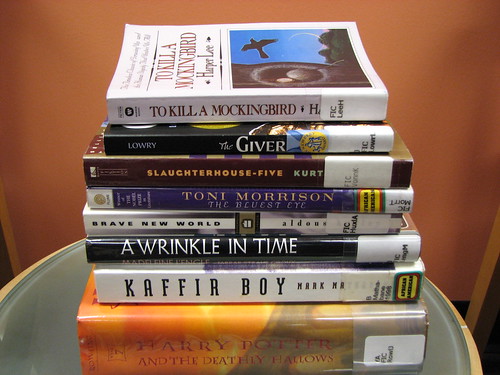

We both had several stories of how our individual stores had fairly competent people working in them: employees and sales people who genuinely wanted to sell the products that we were selling, with a number of additional requirements handed down from up on high. In my own experience, booksellers had the directions to not only greet a customer when they entered the door, but to follow them around the store to be available. If a person asked for a book, we were to lead them to the book, place it in their hands, and do the same for any number of recommended titles. At the register, there was the usual script of asking if the customer had a loyalty card (Rewards Card, sorry), and if they were interested in any of the numerous 'key items' that were located near the register.

If I was a customer walking into the store for the first time, I'd never return.

Stores that sell non-essential items like books, films, clothing and other related things generally mean that the customer isn't pressured to buy something - they're there voluntarily, rather than by necessity, and as such, the customer should be treated as someone other than a source of income for the company: stores such as Borders, F.Y.E., Fashion Bug and numerous others have the wrong approach by forcing items into the hands of customers. The difference that I can see here is in how the customer is viewed by the respective companies: rather than a sales focus, the people on the ground, in the stores should adopt a better customer service model that would allow them to accomplish the same goal without harassing the customers.

I cannot begin to count how many people refused, and have gotten annoyed, or even angry at me for asking if they had the Rewards Card. Several years ago, Borders began their rewards card system, which allowed someone with a card to accrue a certain percentage of their purchases for the holidays and for every hundred dollars, they'd earn $5 back. It's a good system, and I can see the logic behind it: people who use a card will have an incentive to return.

The problem here comes with the requirements and quotas laid down by the company: with a finite pool of people to receive the card, the percentages of new signups will come down over a set period of time. The opposite reaction occurred: quotas went up, and several of my friends were fired as a result, for either signing up blank cards, using the same one over again, to keep up with the demand. Looking back, it's a problem that existed within the company, without taking into consideration the human element: the program turned from something that enticed customers (and continued to do so for the people who did sign up) but also estranged those who weren't interested in the card from day one. The card and the policy behind it failed to adapt to the changes in the environment: as more people signed up, better, more realistic expectations should have been set, and further goals for retention should have been examined.

The problem here, and with the instructions to place books in people's hands, seem to have come from a company that looked only at the numbers, rather than the people who were coming into the store. While I suspect that such practices worked; pointing out books to customers will gain a couple of sales, and should be continued, this only further reinforced the idea that more aggressive policies will equal a resulting sales figure. That comes across to me as being extremely shortsighted: costumers, fatigued with pressure from an aggressive sales front, will go elsewhere, so that they're not bothered or pressured into getting things that they don't want. From where I stood in the company, it seemed as though the management on the district level used a heavy hand when it came to selling their products: push as much out through the door, rather than retaining a population of customers that would return to the store because of the selection of products, the attitude of the sales staff and someone who was satisfied out the door.

As an employee there, I had very little customer service training: no poorly acted videos, program, probationary period, with little idea of the goals and ins and outs of the company as it stood. Quality customer service comes with the people at the front, and the goals that were established for them. Essentially, we were the people handing over the books to the people who wanted them, with little interest in anything else.

There are other companies out there that have done things far differently: Apple, AT&T, Zappos and Netflix all come to mind, as their models are more oriented towards customer satisfaction, rather than sales. Through the job that I currently have, I've attended several webinars and read up on the subject, and it's clear that any business - especially in an environment where consumers are more discriminating with their money. These companies, either in their stores, or over the phone (AT&T is horrid over the phone) are generally very good with their front of the line sales - this breaks down a bit depending on the issue, but for the most part, these places are ones that I've had fairly pleasant dealings with.

Such interactions, with people, rather than an anonymous sales figure or customer service representative are essential. People react positively within their own networks, and generally trust sales and information received from people who they know personally: this is one of the biggest strengths of using social media (and utilizing it well), because people will listen to their friends, and will talk about issues. The same logic can be applied in stores, with a customer sales person that works to make the customer happy, rather than simply filling the company's bottom line. Essentially, information and innovation needs to move from the sales floor up, with a staff that has the latitude to work as needed, rather than from top down requirements. Store and company policy should be informed by the experiences that the employees see.

One of the reasons, I suspect, that the larger book stores are facing hard times is because they haven't needed to understand this dynamic when it comes to their customers, because of their size, and as such, haven't fostered a loyal following. People don't tend to stick with the same stores out of loyalty: prices will help, but the experiences that a person has at any given store will help more. If they're not satisfied, they'll move to a competitor. As such, companies need to be able to adapt to the changes in the market place, and the changes in customer requirements. I suspect that sites such as Amazon.com have raised these expectations somewhat: having pretty much every item ever produced available, not to mention remembering what you purchased and searched for last time. This isn't practical in a brick and mortar store, when it comes to stock, but what stores should be doing is focusing on creating a loyal base of customers, one that caters more to what they are looking for, with the intent on bringing them the best experience possible, and going about that in an intelligent fashion. The bottom line comes down to understanding the customer: they're not idiots.

Understanding good customer service is something that will be essential in the future: companies that can't adapt will simply fade away, while others, with more flexibility, will earn the money that the customers are willing to part with. At the end of the day, Megan and my experiences were similar: the front-line sales staff weren’t able to contribute or implement changes that were needed on our level, changes that could have contributed and translated to a better customer experience. It’s no wonder that some of these places aren’t able to compete.